If there was one common agreement at the otherwise jovial meeting of South Africa’s top business leaders at the B20 – the business stream of the G20 – it was that a wealth tax will never fly.

“It’s a complete non-starter,” said one CEO on the fringes of that B20 meeting in Century City, Cape Town. “For one thing, the government needs money now, and this sort of tax proposal would spend years in the drafting phase.”

It seems so obvious that it needn’t be said, given South Africa’s overreliance on the wafer-thin top strata of taxpayers, and the fact that wealth taxes globally raise precious little. And yet, it speaks to the desperation in government to find anything remotely resembling cash that such a naive idea even made the headlines in the first place.

This apparently emerged from three senior officials in the ANC, who told a special cabinet meeting on Monday that a wealth tax would help fill the R190bn hole left in the budget, after the coalition government torpedoed finance minister Enoch Godongwana’s plan to raise VAT from 15% to 17%. These ANC officials confirmed this to Business Day, apparently, illustrating not only how out of touch South Africa’s largest political party has become, but also how economically illiterate it is.

Wealth taxes were all the rage a decade ago, when French economist Thomas Piketty in his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century proposed a global wealth tax of 1% on people with a net worth of between $1.3m and $6.5m, and 2% on those with even more.

Yet this idea fell radically out of favour, with analysts pointing to the chilling effect it has on GDP growth and jobs. South Africa, of course, has an abundance of neither.

“Many developed countries have repealed their net wealth taxes in recent years,” said Tax Foundation Europe in a research paper last year. This includes Austria, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Finland, Sweden and France. A sprinkling of countries still have one – including Colombia, Norway, Spain and Switzerland – but these wealth taxes have not benefited those economies.

“Countries have repealed their wealth taxes for a variety of reasons: they raise little revenue, create high administrative costs, and induce an outflow of wealthy individuals and their money,” the researchers said.

For one thing, it is a heavy incentive for wealthy individuals to emigrate. This is because wealth taxes generate double, or even triple, taxation – in Spain, the wealth tax lifted the effective marginal rate above 100%. In other words, the entire real return on investment for those people is wiped out.

More critically, for a country like South Africa, the tax foundation argues that wealth taxes “disincentivise entrepreneurship, leading to less innovation and less long-term growth”. Jobs are destroyed, so in the end, all income groups are worse off.

Consider this: in South Africa, there are just 235,000 people earning more than R1.5m a year – 0.3% of the population – yet they pay nearly a third (32.6%) of all the R815bn collected in taxes. If you were to impose a wealth tax that would see even a couple of thousand people emigrate, your tax system would be manifestly weaker.

And, perhaps the final nail in the coffin of the argument is that, for all this damage, wealth taxes raise a vanishingly small amount of money anyway. In 2022, the wealth tax provided just 0.51% of Spain’s total tax revenue, and 4.35% of Switzerland’s.

Waiting for the magical money tree

So if it is such a self-evidently awful idea, why was this even proposed?

The answer is that Godongwana is rapidly running out of time to find another source of funding to fill that R190bn hole before the next-next budget, on March 12. And it has become clear there is no low-hanging fruit to pick.

Monday’s cabinet meeting shot down many of Godongwana’s new budget proposals, including putting a freeze on plans to hire 11,000 new teachers (saving R29bn), delaying new health expenditure, putting the recruitment of doctors on ice (another R29bn), as well as cutting back on salary increases for public servants.

These were “politically unpalatable” options, it seems. And it is true that you’d prefer any government to prioritise getting rid of inefficient middle management in municipalities, ditching blue-light brigades, and tightening the belt of its bureaucracy, than axing people with real skills, like doctors or teachers.

But the truth is, almost all of the trade-offs Godongwana proposes will be politically unpalatable – save for the sudden sprouting of a magical money tree, which some of his cabinet colleagues seem to be waiting for.

Certainly, any cabinet containing the DA would be unlikely to give any wealth tax a thumbs-up. As Mark Burke, the DA’s spokesperson on finance, put it: “Tax increases, including a mooted wealth tax, will chase away investment, shrink our tax base, and ultimately, cause damage to the economy.”

Instead, the hole must be filled by cutting wasteful spending, freezing new appointments, and recovering wasted money, he said.

Treasury, it seems, knows this. Its own documents – particularly the Budget Review that was due to be tabled at last month’s budget that never was – are outspoken about not being able to tax the rich more.

“Raising personal income tax rates is likely to be inefficient as taxpayers make adjustments to reduce their tax liabilities,” it said. “South Africa’s personal income tax collection measured as a contribution to GDP, and the top tax rate, are far higher than those of most developing countries.”

Edward Kieswetter, the commissioner of the South African Revenue Service, also appreciates how fragile the taxpayer compact is. Speaking at an event at the G20 in Cape Town this week, he said a consequence of new taxes is that “we may stifle growth in economic development and also growth in the tax base, which ultimately is the goose the provides the eggs”.

So, don’t tell the ANC, but the jury is in: wealth taxes won’t work. Aside from a possible 1% rise in VAT (which he may not get through now that the DA and other parties have tied their colours to the mast), Godongwana’s only options are cutting spending or borrowing more. And the country’s debt levels are high enough as it is.

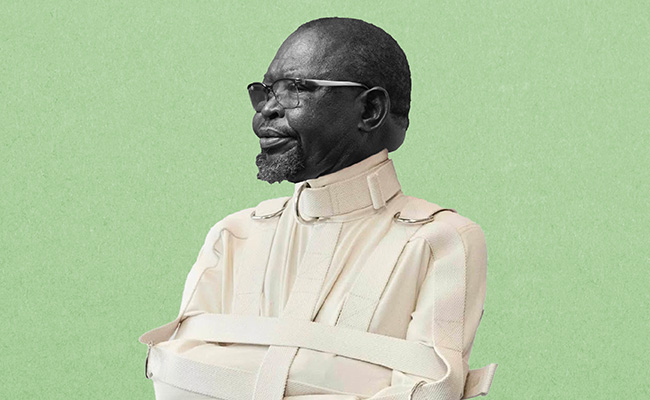

Top image: Enoch Godongwana. Picture: Gallo images, Jaco Marais. Graphic: Currency.

ALSO READ:

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.