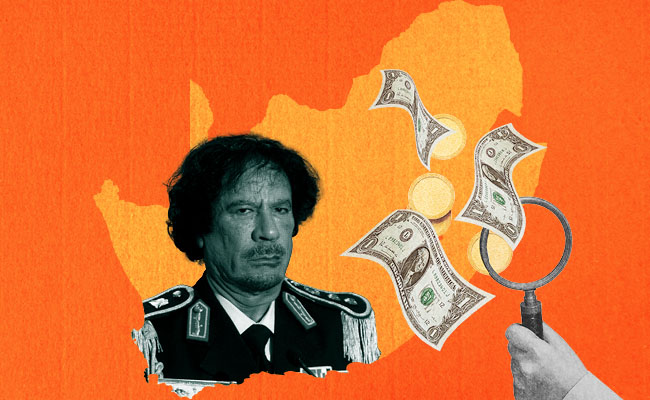

It is an old and universal truth: the bigger the treasure, the greater the secrecy. And here we’re talking about possibly about R2-trillion rand in US dollars, tons of gold and millions of carats of diamonds – more than South Africa’s annual national budget.

Astonishingly, the full truth about the alleged billions that former Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi flew to South Africa shortly before he was assassinated on October 20 2011 has never been fully revealed in an open, regulated society like South Africa’s.

We do know that highly valuable air cargo was brought from Tripoli to South Africa. We know that Jacob Zuma was the president at the time. We also know that Zuma and Gaddafi met several times in the months before his death. And we now have a first-hand account confirming that Gaddafi gave a large sum of money to the ANC’s election campaign in 2009.

The matter has been investigated for more than a decade by our own Reserve Bank, intelligence services and Hawks, as well as the American CIA and other international agencies, but it remains as transparent as mud.

No-one can blame one for suspecting that Zuma personally benefited from the Gaddafi billions, perhaps even that he financed his dozens of court cases and his new MK Party with them.

Two recent books have addressed the Gaddafi billions again: ANC stalwart Mathews Phosa’s autobiography, Witness to Power, and Deon Meyer’s novel, Leo.

Ex-recces

The storyline of Leo revolves around ex-recces who supposedly brought the billions to South Africa and now want to loot it. Meyer did extensive research and writes in a note at the end of the book that he tracked down someone who said he was in Tripoli the day the South African plane landed. Meyer simply calls him Mr X and writes that the man agreed to a telephone interview, only to offer “evasive excuses” each time.

Phosa was elected treasurer of the ANC in December 2007 as part of the Zuma list. He tells of his and Zuma’s several meetings with Gaddafi in his luxury tent outside Tripoli and states that Gaddafi made a “substantial contribution” to the ANC in which he himself was involved as treasurer – something that has so far been vehemently denied by the ANC; a denial that has been repeated after the publication of Phosa’s book.

Phosa says Zuma’s controversial businessman cousin, Khulubuse, was in of one of the meetings, allegedly to conclude military contracts with Libya.

Gaddafi, then chair of the AU, tried to persuade Zuma to support him in his campaign for a second term. He promised Zuma that he would make him foreign minister if he helped him realise his dream of an overarching African government.

After civil war broke out in February 2011, Phosa and Zuma also met with Libyan rebel leaders in an attempt to broker peace. The opposition leaders, part of a transitional government, later told Phosa that they refused to work with Zuma any longer because he had “sold them out” after another private meeting with Gaddafi. They were suspicious about the way Gaddafi had persuaded Zuma to change his position.

Phosa writes that four Libyans were in South Africa at the end of 2012 to discuss the “missing Libyan billions” and adds that Zuma lied to him about it.

In 2013, a CIA delegation came to see Phosa and also asked about the Gaddafi billions. He asked the Reserve Bank to investigate, but did not have the name of the bank or the account number and it came to nothing.

Phosa writes that it was alleged at the time that the Gaddafi money was taken to Nkandla and transferred from there to a bank in Swaziland (now Eswatini). He could not confirm this.

Zuma would not comment on Phosa’s allegations in his book.

More than 62 flights

The most detailed allegations about the billions were made in December 2014 by the then editor of the Sunday Independent, Jovial Rantao. He wrote that his information came from government documents he had reviewed.

Rantao said about R2-trillion in dollars, hundreds of tons of gold and at least 6-million carats of diamonds were transported in more than 62 flights between Tripoli and South Africa. This was handled by a private company that hired former members of the South African Defence Force’s special forces to guard the treasures.

“Several sources have confirmed that the apartheid-era special forces pilots and soldiers have deposed affidavits that are designed to protect them from, among others, money-laundering charges,” wrote Rantao.

According to Rantao, the loot was stored in seven warehouses and bunkers between Joburg and Pretoria. Another R260bn was legally deposited in four commercial banks in South Africa. Some of the loot was later moved to neighbouring countries.

“Those interested in the Libyan loot,” wrote Rantao, “include several high-ranking ANC politicians, several business leaders, a former high court judge and a number of private companies.” He did not provide names.

The Libyan authorities have since appointed a special council to try to track down the Gaddafi loot in South Africa and elsewhere. In 2014, South Africa’s National Treasury appealed to anyone with information about the loot to contact them.

According to an investigation by the Bavarian newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, Gaddafi’s chief of staff, Bashir Saleh Bashir, was believed to be the central figure in the saga and the only person who has the full truth. He is believed to be living in Eswatini.

The Sunday Times reported on April 7 2019 that President Cyril Ramaphosa flew to Eswatini in March 2019 to speak to King Mswati III about allegations that Gaddafi money was transferred to that country via Nkandla. The king initially denied this but confirmed a month later during a visit to Ramaphosa in Joburg that $30m had indeed been transported to his country. (This would be worth about R550m today.)

According to the newspaper, Eswatini central bank governor Majozi Sithole refused to have the cash deposited in the bank. Mhlabuhlangene Dlamini, Sithole’s deputy and a family member of the king, subsequently handled the matter, “highly placed sources” told the publication.

“The deputy governor is involved. He is the one who went with JZ to go and count the money. He took some people at the bank, they apparently flew to King Shaka Airport, counted the money, and brought it back,” a source with links to the royal household and the bank told the newspaper at the time.

The then minister of international relations, Lindiwe Sisulu, called the Sunday Times report a “ghost story”. “When we went to Swaziland there were rumours that the money was in Swaziland. There is no money in Swaziland,” she said.

Zuma knows nothing

The publication Libya Review reported in June last year that investigators are still searching for about $200bn that was moved to South Africa, Kenya, Mali and Senegal, among others. Some of the money was also used to buy stocks and property.

In June 2013, South Africa’s then finance minister, Pravin Gordhan, said he had agreed with the Libyan government that “Libyan funds and assets” in South Africa would be returned to Libya. It is unknown whether any such transfer has been made and National Treasury has not yet responded to my inquiries.

Just a week after Gordhan’s statement, Zuma said in response to a question in parliament that he knew nothing about the Gaddafi money. “I don’t know why Gaddafi or Libya’s money is here. I don’t know. I was never involved in what caused the money to be here,” he said.

When asked whether the ANC’s head of security, Tito Maleka, was involved in the saga, Zuma replied: “I don’t know. This has not come to my ears, that some ANC head of security was involved. So I don’t know about it.”

This is Zuma’s old strategy: deny, deny and deny, until your interrogators get tired and stop asking questions.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.