In 2016, Wilhelm van Rensburg had just started his career as an art curator at Strauss & Co. While working at the auctioneers one day, he was visited by a dealer, who brought in an original artwork he wanted to sell.

Van Rensburg recognised Walter Battiss’s Mapungubwe immediately. As a student in the 1970s, he’d lived across the road from the Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG) in Joubert Park, then a thriving multicultural area.

“I was literally in the museum every day of my life on the way to university or on the way back, except on Mondays when the gallery was closed. So I knew that collection like the palm of my hand,” he tells Currency.

“I said to this person: ‘Are you sure this is not supposed to hang in the JAG?’ He said: ‘No, it came from a very prominent collector who’s had this work since 1992.’”

Van Rensburg was immediately suspicious, and called the registrar at the gallery to check, knowing what hall the painting would have been hung in.

“‘She said, ‘Let me go and see,’ and then said it wasn’t there. So I said: ‘Go to the storeroom,’ and she came back after a while and said it wasn’t there either, and then I said to her: ‘Well, I have it in front of me.’”

At that point, Van Rensburg says, he wondered whether the artwork was a forgery; but when he turned it around he saw the old canvas – a hard-to-fake sign of originality. As for the dealer, embarrassed, he took the painting and left.

“I should have impounded it, but by law we’re not allowed to – that would have constituted theft. So I had to give it back. I heard later that the painting did go back to the gallery,” says Van Rensburg, who believes the dealer – whose identity he has asked to remain secret – acted in good faith.

It’s no small irony that Strauss would have found itself in hot water trying to protect a collection that belongs to the people of Johannesburg, under a deed of trust established more than a century ago. This same collection, worth hundreds of millions of rands, has become perilously vulnerable to theft, decay and criminal neglect by the city meant to steward it. And the risk has ramped up exponentially in the past five years under the city’s increasingly dysfunctional department of arts, culture and heritage, headed by a man named Vuyisile Mshudulu.

For starters, the art gallery building in which the collection is housed in Joubert Park – an area which today is one of the most crime-ridden parts of the city – is in “deplorable condition”. Designed by architect Edwin Lutyens – a contemporary of Sir Herbert Baker – it is a leaky wreck, thanks to numerous half-baked attempts at restoration.

This is the main reason why a body called the Friends of the JAG (set up in the 1970s) and the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation have enlisted the services of law firm Webber Wentzel to try force the city to move the gallery’s artworks. They were hoping to do so before this year’s rainy season starts in earnest, but given last week’s typical highveld storms, they may be too late.

In a letter to Joburg mayor Dada Morero, Mshudulu and the art gallery committee chair Joseph Gaylard dated August 28, Webber Wentzel writes: “As things stand, the [City of Johannesburg] and the Art Gallery Committee have dismally failed to preserve the JAG art collection and have neglected their duties to create a conducive environment for the public of Joburg to enjoy the artworks.”

As a result, the city, and the gallery committee are “in breach of the public duties vested in them by the deed and the constitution”, the lawyers write.

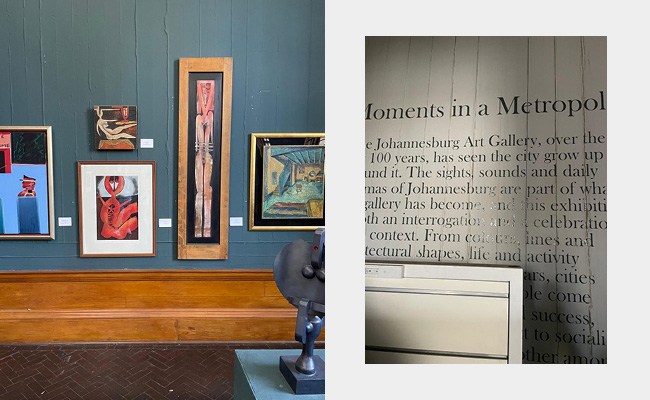

Insiders consider chief curator Khwezi Gule to be at least partly responsible for JAG’s increasing decrepitude. A tour he led in June this year found the exhibition halls “to be in dire condition with limited, if any displays”, say these insiders. Of the 15 exhibition halls in the JAG, only two were operational, while almost all of the gallery’s 9,000 artworks are in storage. As it stands, only 1% of the collection is actually visible to the public.

And here’s the other problem: half of the storage rooms are susceptible to leaks, flooding and black mould. During heavy rains, the art collection has to be routinely moved around to makeshift storage sites – including the JAG’s old coffee shop.

Last year, former curator Christopher Till managed to move what is known as the Brenthurst Collection out of the JAG. That collection – now back at Brenthurst – is a valuable assemblage of mostly African art that was paid for by the Oppenheimer family, which founded Anglo American in 1917.

Till recalls water running down the walls, and dead rats and pigeons lying about. In one part of the historic building, the original cork flooring had been removed, as had the copper that once adorned the roofs.

“It was an absolute disaster. That gallery is dead,” he tells Currency.

It’s little wonder that hardly anyone goes to see the collection any more. A mere 5,000 people traipse through the building each year. That is far less than 1% of the 7.2-million punters who poured through the halls of Paris’s Louvre in 2023, and less than 3% of the 189,003 visitors who descended on Cape Town’s Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town.

Clearly, it’s not just rain that has made the collection so vulnerable; it is mismanagement on a grand scale and a pig-headed refusal to do the right thing on the part of city leaders – an approach which is only accelerating the decline of Johannesburg itself.

A ‘colonial vanity project’

So why does any of this matter?

Well, for starters, the collection is the richest in Africa – at one point, the most valuable in the southern hemisphere – with a price tag running into the many millions. For a city with increasingly frayed accounts, which is effectively running on borrowed credit, that’s a hugely valuable resource – not just culturally, but financially.

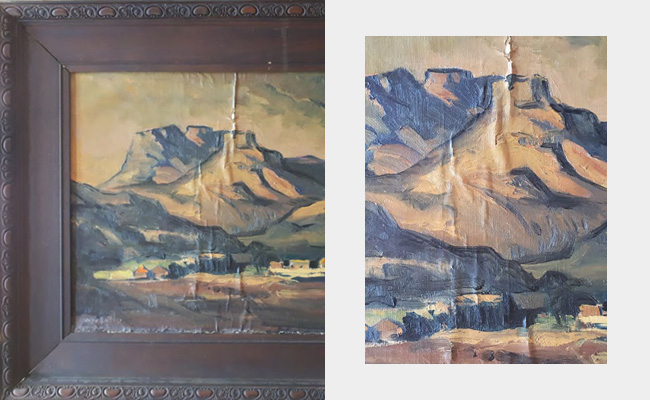

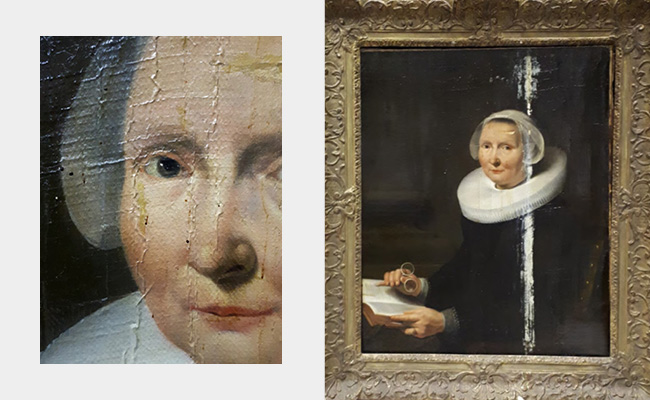

Currency has established that a clutch of only 20 damaged artworks – for which Ekkehard Hans provided a restoration quote in 2018 – would in pristine condition fetch R32m conservatively, according to Everard Read chair Mark Read.

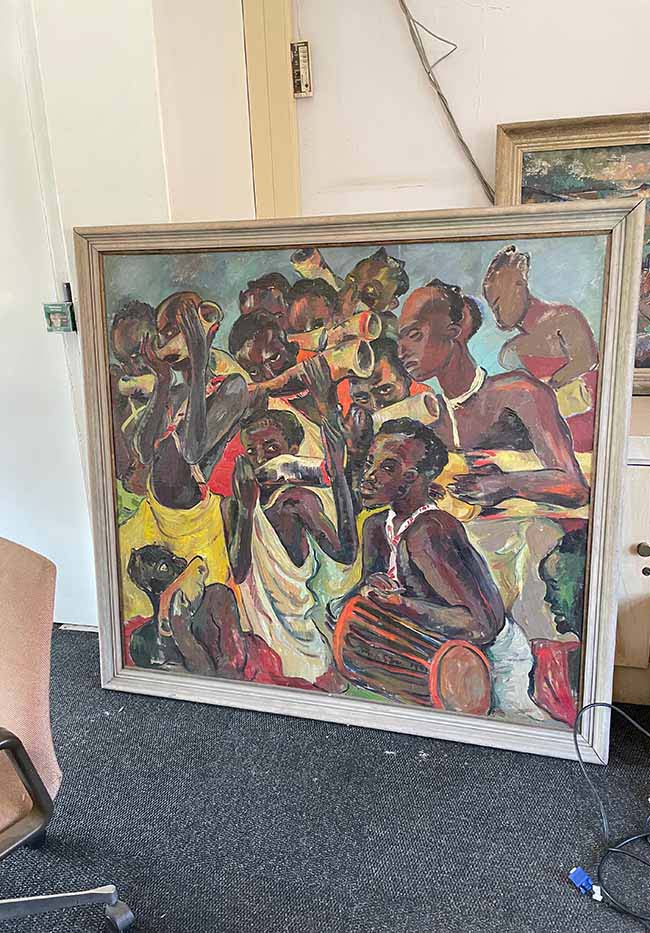

Those 20 works – pictures of which we’ve included in this feature – include a Munnings (estimated value: R2.5m), a Burne-Jones (R2.4m) and an Irma Stern (R19m).

In the end, the restoration work didn’t go ahead because the insurers wouldn’t pay out, given the state of the JAG building. But if you extrapolate that sort of value to the 9,000 pieces in the collection, you’re talking big numbers.

And yet, evidently, some in the Gauteng government don’t think any of this matters. Mshudulu – under whose remit the gallery falls and who has consistently ignored requests for interviews or comment from Currency – allegedly labelled it a “colonial vanity project”, for one.

That’s an easy line to argue in a city whose issues – and budgets – are increasingly existential: no water in public sector hospitals, no electricity for hundreds of thousands at any one point in time, no housing for the indigent, an immigration crisis.

And that’s before the lesser but more visible symbols of decay: potholed streets, pavements that no longer exist, litter and dysfunctional streetlights that condemn many of the unsafe roads to darkness.

What value an Irma Stern, when there are life and death matters to consider?

Part of the problem, however, is that nobody in the JAG actually knows the true value of the collection – and city officials like Mshudulu seem to have bent over backwards to keep it that way.

Mysteriously, the city has refused to divulge a full catalogue of the art, ignoring Currency’s request for the catalogue. This isn’t a coincidence; the city also fobbed off similar requests by the Friends of JAG – an implied arrogance which belies the fact that the collection belongs to the city’s residents, not the city officials who seem intent on treating this as their own.

Insiders suspect that one reason for this is that some of the more valuable artworks, like Walter Battiss’s Mapungubwe, have been stolen. Whether this would be by city officials, aware that nobody could hold anyone accountable without a proper catalogue, or outsiders exploiting the city’s abysmal management of the collection, is unclear.

Those officials who refuse to reveal to the public what assets lie in this collection are not just indicative of an arrogant disregard for the city’s residents; they appear to also be violating the government’s own accounting rules, which prescribe how to classify and record heritage assets.

Mshudulu, who still earns a salary from taxpayers, may be the man whom critics point to as the biggest obstacle, but his obdurate stance of secrecy is not a unanimous one, even within the city’s structures.

Employees in other areas of the city’s cultural divisions, who spoke to Currency on condition of anonymity, remain suspicious about the city’s motives for refusing to be transparent. It’s in the interests of a few select people in the city’s upper echelons, they say, that no-one knows how many artworks there are, where they are or what they’re worth.

The irony, of course, being that the artworks don’t actually belong to the city at all.

Culture wars

According to the original 1908 deed of donation from lady Florence Phillips – the powerhouse wife of mining magnate Sir Lionel Phillips – the art gallery was entrusted to the city as the custodian of the art collection, but the art itself belongs to the people of Johannesburg.

The gallery, Phillips hoped, would be a space of moral and cultural upliftment, in keeping with late Victorian, Edwardian notions of “moral didacticism”, according to Federico Freschi, executive dean at the faculty of art, design and architecture at the University of Johannesburg.

The collection was initially European-focused, with everything in the Western canon from the Dutch golden age to impressionists, to works by early South African modernists and then major contemporary international artists like Picasso and Andy Warhol, Francis Bacon, Auguste Rodin and Claude Monet.

Given its initial Eurocentric focus, you can see how easily the JAG became a battleground in the culture wars around its value to society, especially after democracy in 1994. Which is one reason that it’s been so vulnerable to officials with ulterior motives.

But from the 1970s onwards, the JAG became focused on building up a collection of great African and South African names, from artists like Gerard Sekoto, Sydney Kumalo, Jacobus Pierneef and Irma Stern to William Kentridge.

“It’s an extraordinarily rich and diverse collection and in many ways would, in a functional city, be part of the pride of the city – even in a postapartheid, postcolonial context,” says Freschi. “There are ways of using the collection to question and to challenge.”

Legally, the artworks are entitled to be protected under the National Heritage Act too, inscribed as national heritage assets.

Freschi argues that a properly functioning public gallery can “inspire and vex, complicate, and excite; bore and enrage”.

“Art can really prompt you to see the world in new ways, and it doesn’t matter who you are. I think this is one of the casualties of the culture wars; that ‘X’ should be cancelled because it’s irrelevant. That is censorship and you really have to enable people to make up their own minds. And how can they do that if they can’t see the damn collection?” he asks.

Freschi is acutely aware of the country’s manifold complications. “South Africa carries this weight of intergenerational trauma and anger and tension and poverty – yet there’s this thing that connects us as South Africans regardless of who we are and one of the ways to express that is through our creativity.”

It’s one of the reasons Freschi moved back to Johannesburg last year from New Zealand, where he spent four years in Dunedin as head of the college of art, design and architecture at the Otago Polytechnic.

Yet, the JAG is losing the opportunity to add value to the lives of children who are living in the degraded urban environment around the gallery in Joubert Park. “It’s more than just about the collection: it’s a thing that has enormous power to shape and influence,” he says.

That function has now largely been taken over by Joburg’s privately-run commercial galleries – but their focus, ultimately, is to show pieces that are going to sell.

Museums, when they work, also create jobs, he says – a rare commodity in a country with 32.1% unemployment.

“Yes, it costs money – but it costs money because it represents a value that can’t be quantified. If it changes one child’s life, and they make their way to us and finish a fine arts degree, and go on – those are the things you can’t quantify because they are hidden in plain sight.”

Demolition by neglect

So how did it all go so wrong?

Why, if the art gallery had so many committees in its orbit – the Anglo American Johannesburg Centenary Trust, the art gallery committee, the Friends of JAG, the city itself – has it all fallen apart?

For a start, there’s the peculiar governance black hole into which the gallery falls: the city doesn’t own it; the Friends of JAG don’t own it; the gallery employees don’t own it.

Intriguingly, the tension between the city and the gallery isn’t even a new phenomenon – it was there from the outset.

The gallery, says former curator Till, “opened unceremoniously because there had been such bad blood between Lady Phillips and the city because they wouldn’t finish the building”.

Money for the building was made available by the city, while the collection remained within the control of the art gallery committee, which operated under the deed of trust. The way it worked was that pieces for acquisition were presented to the art gallery committee on which the mayor was supposed to sit. Even in Till’s time – he joined as chief curator in 1984 – the mayor “never did”.

Over the years, however, insiders say the art gallery committee was sidelined, so that it has become little more than an acquisitions committee, stripped of its powers.

The Friends of JAG, meanwhile, became increasingly moribund as directors of the organisation, who were meant to supervise, died and were not removed from the directors’ roll.

It means, as part of its pro bono work over the past two years, that Webber Wentzel has spent much of its time simply trying to remove dead directors, which is something of a nightmare process.

Eben Keun, a member of Friends of JAG, explains: “The system had worked because there was sufficient investment and a kind of integrity and understanding of what the intention was. When the wheels started coming off, it was very difficult to apportion blame or to identify who was at fault because it fell into the gaps.”

So, what about the Anglo American Johannesburg Centenary Trust, set up in 1986 to fund the acquisition of artworks? After all, with the backing of the mighty mining firm, it helped buy about R20m worth of art, which the trust reckons today is conservatively worth R100m.

It turns out the trust hasn’t financed any purchases since 2016 “due to concerns about the deteriorating condition of the JAG building and the risk of damage to the artworks”, the trust’s chair Michael Murray tells Currency.

Asked what it’s done to intervene, Murray says the trust was willing to pay R5m more than two years ago to move not only the trust-funded artworks but the entire JAG collection to a secure new storage place “pending either the restoration of the JAG building, or the identification of an alternative venue to exhibit the artworks”.

But that funding was contingent on the city giving a comprehensive inventory of all JAG artworks. Again, that didn’t happen, as the city refused to reveal what lay in the collection. The result is that even if the trust were to pay R5m today, that wouldn’t be nearly enough to fix the problem.

Asked whether the trust was too hands-off in overseeing the assets it funded, Murray says: “Not at all,” arguing that the Trust’s mandate was limited to buying art. “It does not have any mandate or right to compel the city to move the artworks.”

For Freschi, the JAG’s seemingly inexorable slide has occurred because, for too long, looking after it became just too hard for the city officials tasked with doing just that.

“And then you can find all manner of excuses, like apartheid and colonial settler stuff. But that’s glib and unsatisfactory,” he says. “I think the main problem is just abject mismanagement. And the effects of that are exponential.”

This special report on the Johannesburg Art Gallery is a continuing joint investigation by Currency and the Daily Maverick.

To read Daily Maverick’s take this week, click here.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.