“Slippage” and “pressure” might be the keynote descriptions of the 2025 budget due to be delivered next Wednesday.

“Every year we say ‘this is going to be a difficult budget’, but I think this year is actually going to be a difficult year,” says Xhanti Payi, economist at PwC.

The key budget figure in the recent past has been the deficit: the amount by which expenditure exceeds income. The reason it’s such a crucial figure is that after decades of low growth and habitual over-optimistic forecasts about anticipated growth, South Africa’s national debt has now ballooned to levels that would make even developed countries with relatively stable budgets nervous.

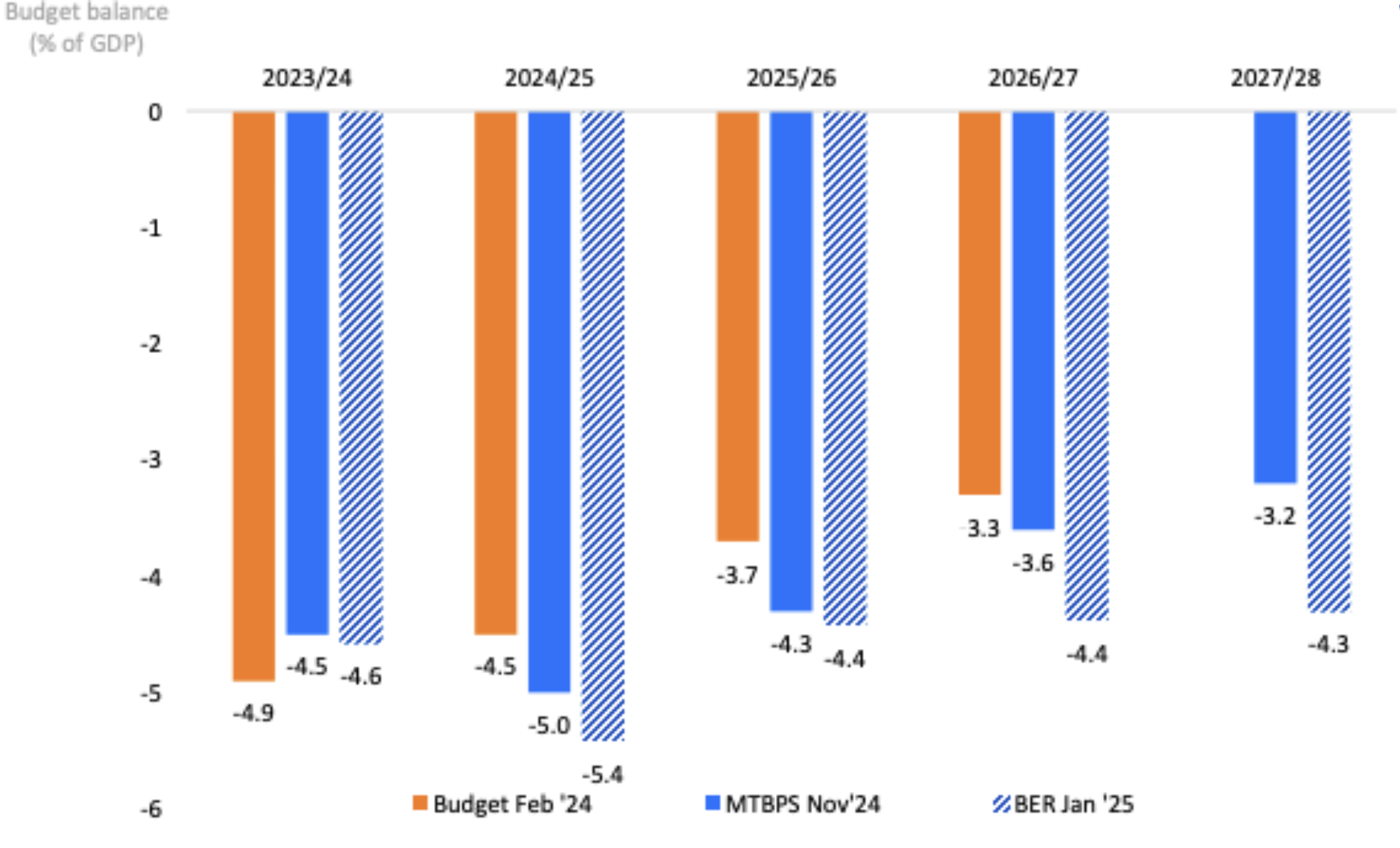

But in the very recent past, the news on this front has been good: the deficit has been coming down and, even more encouraging, the difference between the budgeted deficit and the deficit after the actual outcome has declined. This year, however, that trend will probably be reversed, giving rise to “slippage”.

The “pressure”, on the other hand, stems from four different directions: the final agreement on the public sector wage increase, which was slightly higher than budgeted; a general need across state-owned enterprises and departments to increase infrastructure spend; the pressure to increase state income support; and, most recently, the need to increase the defence budget in light of South Africa’s involvement in continental conflicts.

An increase in the deficit was signalled in the medium-term budget policy statement (MTBPS) in October, but it may even come in slightly higher than forecast. Payi says PwC is estimating the deficit to be about R40bn, with lower VAT receipts the main culprit at R22bn, and the fuel levy bringing in about R12bn less than expected.

Other economists agree, with the Stellenbosch Bureau for Economic Research (BER) now estimating that the deficit will come in at 5.4%, as opposed to the 5% figure estimated when the MTBPS was presented.

The debt burden

This is a disappointing outcome in a year in which it was hoped that one-off benefits from the move to the two-pot retirement system would inject a bit of life into the retail sector. Clearly it did, but not enough to outweigh larger economic pressures, the most notable of which is that the economy is not bouncing back as much as hoped, at least so far. The boost to personal income tax from the two-pot pension fund withdrawals is likely to come in at about R12bn against a budgeted figure of about R5bn.

The overall result will be a higher national debt burden, which is worrying because one of the largest and fastest-growing items in the budget concerns debt service costs. These are now larger than all corporate income taxes paid in South Africa and they constitute about 20% of revenue. Per day, the country is shelling out about R1bn just on its borrowings.

Consequently, and above all else, economists will be looking to finance minister Enoch Godongwana to continue a path of fiscal consolidation, itself dependent on what sort of growth rates we hit in the next few years.

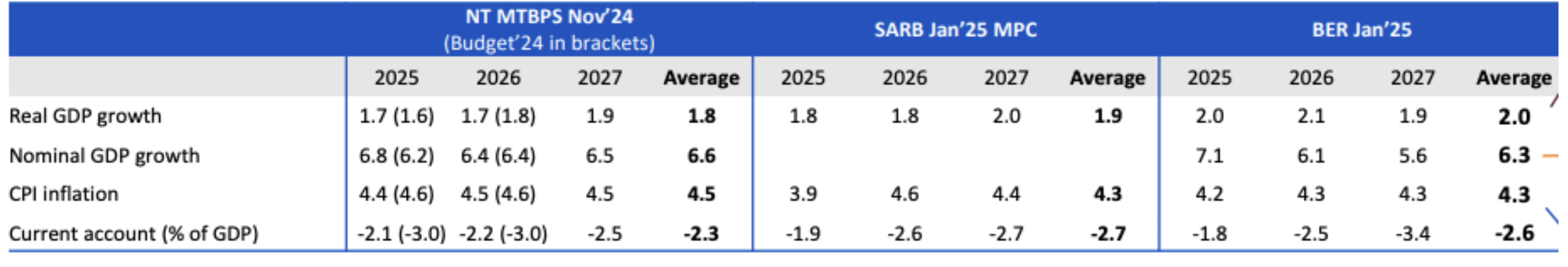

Already, differences are emerging in anticipated growth levels among economists. The current expectation in the medium-term budgeting process is growth of 1.7% in 2025, with the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) estimating slightly higher and the BER estimating higher still.

Some economists suggest that growth of 2.2% won’t be impossible in 2025, and it will be one of the interesting aspects of the budget whether Godongwana is confident enough to ride that wave. The National Treasury’s optimistic longer-term growth forecast would be a significant indicator of record “buy-in”, the BER’s Shannon Bold and Lisette-IJssel de Schepper suggest.

On the expenditure side, Payi is hopeful for a more than 1% increase in the defence budget, saying “that whole thing that happened in [Democratic Republic of Congo] is probably very noisy at the moment”.

But there’s also pressure to support the new and controversial National Health Insurance scheme, to increase the social relief of distress grant, particularly after the Pretoria high court has declared some grant regulations unconstitutional, and to introduce a basic income grant.

Other talking points will be discussions about lowering the SARB’s inflation target and the possibility of a “fiscal anchor”, which would stabilise government debt by maintaining sufficiently large primary surpluses over the rest of the decade. The latter is important because of the DA’s support for the proposition in the government of national unity (GNU) and the fact this this will be the first budget under the GNU.

The upside of winning the fiscal sustainability battle could be an upgrade in our sovereign credit rating over the next year or so. The downside is really not worth considering.

Top image: Finance minister Enoch Godongwana. Photograph: Gallo Images/Brenton Geach. Graphic: Currency.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.