It’s a significant moment in the development of a nation when ordinary citizens become the target of organised crime. Even if they just feel that way.

Law-abiding citizens are always on the wrong side of organised crime, however indirectly. When the construction mafia forces dozens of construction projects to a halt, citizens bear the brunt of the subsequent housing shortage; the same for clinics or bridges that aren’t completed.

When trains are burnt, we can’t get to work, nor can those who work for us. We know we’re victims, but we also know we’re not the primary victims of the crime.

But when someone in our residential area, say, is grabbed on the street, and a ransom demanded from the family, the threat becomes a lot more real, and a lot more direct.

‘Not our problem’

Unfortunately, South Africans have long learnt to live comfortably alongside the obvious operations of organised crime. Cape Town is a world murder capital, yet middle-class Gautengers move down to the metro in droves “because it’s safer”. And it is – for them. The Cape’s high murder rate, apart from the massive influence of alcohol-fuelled knife and gun fights in taverns, is a result of gang wars. The conflict is generally localised.

Even kidnappings for ransom were previously an issue of fascination, given their specificity. At one point, it became relatively common for wealthy Muslim businessmen to be grabbed and for millions in cash to be demanded for their release. Some of these detentions lasted for months, but the information that filtered through to the public was minimal and incomplete, usually because the victims’ families were too afraid to go public.

Some of these cases were linked to a notorious Mozambican syndicate, allegedly connected to Esmael Malude Nangy, who was arrested and tried in Centurion early last year.

Some researchers and police members say that the entire technique of high-level kidnappings for ransom was imported from Mozambique, where criminals focus almost exclusively on cash-heavy businesses; for example, the wave of kidnappings of Portuguese butchers in Gauteng.

A real wave or just a perception?

Still, it appears a new focus has emerged, given the recent wave of kidnappings in Stellenbosch, the Eastern Cape and Gauteng. In the Western Cape alone, 233 cases of kidnapping were reported to the police between April and June, and in nine of these cases ransoms were demanded, while in another five some other form of extortion was used.

A Stellenbosch student was recently kidnapped at 2.40am on a Thursday from Plein Street by two men in a vehicle and released a day later after her family paid a ransom. In June, a suspect was arrested in Caledon following the kidnapping of two students in the Franschhoek Pass. In two other incidents, two Stellenbosch students and a cyclist in Stellenbosch were kidnapped and in both cases they were transported to Grabouw, from where a ransom was demanded. An elderly British tourist was also kidnapped and released.

The country anxiously watched the kidnapping of Alize van der Merwe, who was held for six days in September in the Eastern Cape, until she was released along with a foreign tourist, Xiaomei Tian.

It raises the question whether the middle class has recently become a real target, or whether the media profile of a white woman captured from Stellenbosch is simply that much higher than the kidnapping of a black woman from Lusikisiki, say.

We indeed have a problem

So we asked three seasoned crime experts about this. Their answers are sobering:

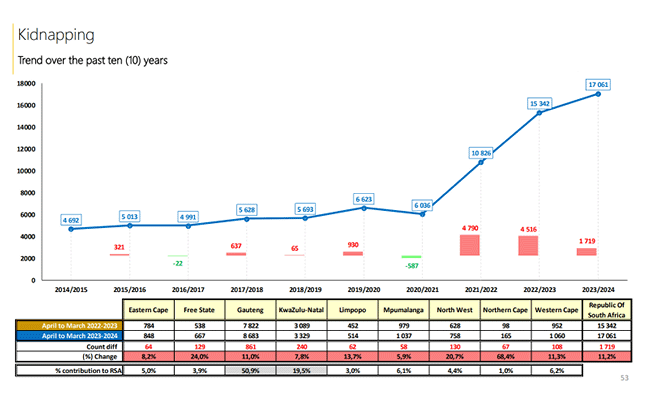

“The number of kidnappings reported to the police has increased by 300% over the past decades. That’s dramatic. It increased by 10% just over the past year,” says Lizette Lancaster, a senior researcher at the Institute for Security Studies (ISS). “While initially it was transnational syndicates demanding ransoms for kidnappings, increasingly it’s local groups doing it. It’s just local criminals who see that other people are making easy money from this.”

While these copycat kidnappers may be less sophisticated, they “either target people about whom they have information, or people who simply look like they have money, and therefore it becomes more random”, says Lancaster.

“It’s happening more and more with people who are in the wrong place at the wrong time. The targets are people who run cash businesses, and increasingly middle-class people who look like they have money.”

Ian Cameron, DA MP and chair of the portfolio committee on police agrees that there has been an increase in attacks on the middle class: “I think it’s an extremely attractive business move for many of these criminals, because it’s low risk in terms of them potentially being fatally wounded in the process, say, than in an attempt to rob a shop.”

Cameron says criminals can make more or less the same amount of money, given that in many cases the ransoms are paid. “Also, importantly, the punishment, if you were to be caught, is extremely low. You can’t compare it with other crimes. It’s also easier to do than stealing copper cable. You’ll eventually make good cash, and the risk is low.”

Jenny Irish-Qhobosheane, a researcher at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Crime, also says there are two types of syndicates at work: the highly professional transnational syndicates, who only target the ultra-wealthy with lots of available cash, and what she calls the local copycats – “We see it even here in the townships with children being kidnapped, even though their parents don’t have much money.”

Kidnapping, the baby of all mafias

Irish-Qhobosheane is one of South Africa’s leading experts on the massive extortion networks that have developed over the past 40 years, particularly in Cape Town and Gauteng. In Cape Town, she writes about four major networks in her reports – the oldest being the nightlife security network, allegedly run by Cyril Beeka initially, and later allegedly by Mark Lifman, Jerome “Donkie” Booysen and Nafiz Modack.

Then there’s the extensive transport extortion, involving almost all taxi associations, which extort each other and any other transporters who stand in their way, such as large bus networks. Taxi bosses will even go so far as to intimidate private individuals who give others lifts to work.

The third major extortion network operating in Cape Town and Gauteng is the newest one, the so-called construction mafia, which has violently wedged its way into the industry through so-called local committees, with the support of established local gangs. This mafia, which initially emerged in KwaZulu-Natal, summarily enters a large construction site and demands that at least 30% of the contract work comes to them, as well as protection money in some cases.

Now, too, we have the water mafia in Gauteng: a gang organisation that violently demands contracts and work for its members, mainly from Rand Water, the parastatal that controls Gauteng’s water networks. It was this criminal network responsible for the murder of Rand Water executive Teboho Joala.

The last network Irish-Qhobosheane refers to involves local extortionists: street gangs that initially started demanding protection money from foreign spaza shop traders around the 2008 xenophobic attacks. They started with Somalis and, after Covid, began demanding protection money from local traders, then from any businesses in the townships, and even ordinary private citizens.

She says police are most worried about the enormous increase in gangs dominating every aspect of township life. Here she frequently refers to Boko Haram (not related to the Islamic movement) in Alexandra, as a classic example.

As for kidnapping, Irish-Qhobosheane says it’s “a little bit sophisticated in the sense that you need a house somewhere to hold the person, and grabbing the person is a bit of a risk, which is very similar to the risks in car hijackings and cash-in-transit robberies”.

‘Let’s go for a ride’

Yet all researchers are keen to emphasise that many of these kidnappings are not planned, but are rather extended hijackings, or robberies, where too little loot has been yielded. According to the statistics, only 5% of kidnappings were entered into with a ransom in mind.

Take the case of two or three hijackers who hijack a professional in a BMW on a Friday night in Johannesburg. They drive around with the driver with a pistol against his neck, from ATM to ATM, to withdraw all available money from his credit card, his checking account and his savings account. After he’s increased all his cards’ limits and cleared his overdraft facility, they have R120,000. That’s too little to divide between three people for a high-risk robbery and three hours’ work.

So they take him to an apartment in Hillbrow, where they also force him to activate and withdraw from one or two loans for which he’s been pre-approved. Now they have R250,000. But time is running out – it’s Saturday morning and his family is starting to look for him. They then threaten the family, and walk away with more by Sunday.

Was it a kidnapping? Technically, yes. Is it reported as a kidnapping? Sometimes – if it’s reported at all. According to Irish-Qhobosheane, the police still have a lot of work to do to sort out kidnapping statistics more accurately. There is a large overlap between kidnappings for ransom and extended robberies, hijackings and abductions, which are usually kidnappings within a family, for example.

What worsens the evidence gathering is that a large number of kidnappings for ransom are never reported to the police, out of fear of retaliation, and sometimes also because people find it humiliating that they were forced to pay over a large sum of money to criminals.

Are they coming for us?

This all brings us back to the question of whether this dark world is directly targeting the middle classes, in their neighbourhoods and homes.

The ISS’s Lancaster believes that even criminals don’t want to infinitely complicate their lives by kidnapping a middle-class child. Such a situation would stir up tremendous emotion in a very resourceful community; it resonates in the media like few other cases, and puts enormous pressure on the police and politicians to do something.

“In our residential areas, it’s still at a very low level, but be vigilant if you’re a businessman who is mobile and works with cash. Also be aware of what’s happening near you. If Muslim businessmen or Portuguese butchers have recently been grabbed in your area, be alert,” says Lancaster.

Cameron worries about the well-developed criminal networks in the Eastern Cape, in conjunction with questionable police management. Cameron says the commanders of the kidnapping unit in the Eastern Cape are themselves under suspicion for various crimes.

However, he is also surprised by the police response in the Van der Merwe case: “I was really impressed with the police and especially the Hawks in the Eastern Cape’s urgency to handle the case. They really went out of their way not just to do what they could, but to work with the private sector as well. It’s encouraging for me to see that the new police minister [Senzo Mchunu] feels so strongly about it and involves all stakeholders that he possibly can. This is something we haven’t had in the past.”

Irish-Qhobosheane also believes progress has been made. “There have been many significant arrests around the larger networks. Several key criminals in the kidnapping networks have already been taken into custody.”

However, warns Cameron: “I think there’s significant involvement in all these structures from prisons, and that makes it complex, because many of the activities are co-ordinated, or approved, or instructions are given from correctional centres.”

He also believes that though there is good co-operation in places, the police, the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) and correctional services are still far too fractured to be effective. “There isn’t an integrated effort,” he says. “That [relationship] between the police and the NPA, to purposefully remove certain key persons from circulation, so that you can put an end to the trend, in my opinion … it doesn’t exist.”