At a braai last weekend, I spoke with a professional soldier, a high-ranking officer in the South African National Defence Force (SANDF), about his life and career. Before 1994, he was a young officer in the old military, the SADF.

I know him as a patriot who was always optimistic about South Africa, and who acknowledged the inevitable growing pains for the complex transition of the military post-1994.

But when I saw him last, he was pessimistic about the SANDF’s prospects, and said he could no longer turn a blind eye to the self-important, egotistical mentality in the military’s leadership structure. “The golf-day mentality”, he called it, referring to the generals who played at a festive golf event two weeks ago while 14 of their troops lost their lives in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

“You see it in the rollout of new uniforms,” he says. “The generals wear new uniforms, the troops have to buy their own boots because there’s no money to buy boots for them. It’s a typical Russian mentality in our military. They are so important that they can’t talk to the troops. They are so important that when they arrive at a unit, there are honour guards, red carpets. They are escorted, they are given gifts, they are considered so important that they create a kind of Idi Amin myth.”

The conversation stayed with me so much that I decided to speak with a military expert – Professor (Lt-Col) Abel Esterhuyse, head of Stellenbosch University’s department of strategic studies – about where the defence force finds itself, and how it can transform to become a functional military again.

What went wrong in the DRC?

We have been warning for the past year that the deployment to the DRC was an ill-considered deployment that should not have taken place because our military no longer has the capability to project force over that kind of distance. We don’t have the strategic air capability to support our forces over that distance. When we talk about support, we’re talking about four things: intelligence, which we don’t have the capability for; we also don’t have the capability to support them logistically; nor with air support or specifically close air support; and we don’t have the capability to support them medically.

All four of those realities came true [in the DRC] and we must hold our military leadership ethically responsible for the deaths of our soldiers, because they were warned about these things and they wiped their backsides with it … excuse me, but I’m getting furious about this …

The fact of the matter is, every military analyst warned about this, the media wrote about this. You didn’t need to be a rocket scientist to see a mess was developing here. And it was so sad for me to see in parliament, during the defence portfolio committee session this week, that the politicians were trying to hold the generals and the minister responsible for the deployment, while parliament approved that very deployment!

They don’t understand that they made the decision, because they approved it, parliament approved it, and now they’re asking questions as if the minister and the generals are responsible for it.

I’ve been wondering how a peacekeeping force ended up so deep in a conflict, fully integrated by a country’s military. Was this a normal peacekeeping deployment?

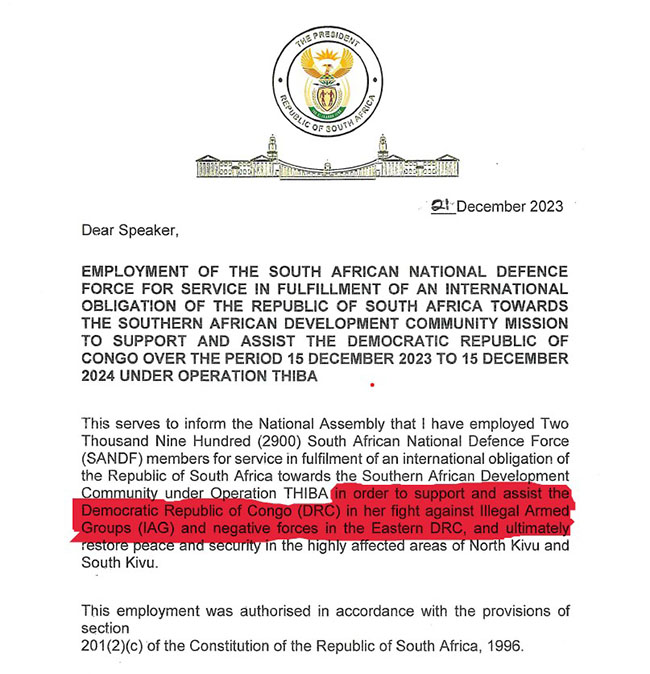

Not at all. I’ll go find you the ministerial authorisation, the submission that Cyril Ramaphosa made to parliament – the president himself! He had to explain to parliament why he was deploying the military. If you look at that briefing, you’ll quickly realise he set it up outright as a combat mission. There’s no wording around a peace operation in that document that was approved in parliament. They’re lying to the public!

How would South Africa’s military look if you could transform it?

The first point to make is that the military in structure, in personnel, in technology, must be fit for purpose for the tasks it needs to do; and, second, it must be aligned with the budget … and then we’re not talking about the budget they want, but the budget they receive.

But what is it that the military must do? Is it still the same as 50 years ago?

Well, historically our military has always been linked to three functions. One is that our military had an internal stabilisation role, whether it was the 1922 strike, or the apartheid government suppressing black uprisings, or the current government dealing with lack of service delivery … our military has always had an internal stabilisation role …

But even a conservative general like Constand Viljoen resigned because he didn’t want to fight against his own people in the townships. Is it a good idea for the military to be involved domestically, and also do police work?

It’s not desirable and the philosophical reason is very simple: militaries work with an adversarial mindset. It doesn’t matter where you deploy them, when they do their assessments, they ask who’s the enemy. So the moment you deploy them domestically, you work with such an adversarial mindset and that’s not good.

That being said, in developing states, the domestic deployment of the military is a given. You can’t get away from it. The dream that the police handles domestic security and the military handles foreign security is exactly that, a dream. In developing countries, both the police and military are underfunded and can’t do their work properly, so they must help each other.

The second function that the military historically fulfilled was dealing with threats from Africa, whether it was Jan Smuts with German South-West Africa, or the apartheid government with Angola, Zimbabwe and Mozambique … Part of the problems we’re sitting with now is that the government was naive after 1994 to think that South Africa no longer needed to handle threats from Africa.

Africa was historically always a threat to South Africa. It manifests in different ways today. The biggest problem is probably illegal immigrants and instability on the other side of our borders, and I’m specifically referring to the situation in Mozambique.

Third, we must also handle threats from outside Africa, and I’m thinking especially of cyber threats. The military probably doesn’t play a primary role there, but it has nevertheless been designated by the government as the primary agent against cyber threats to South Africa.

I wonder about the severely reduced budget for the military. Could one create this kind of military you’re talking about with the right people in charge, and the political will?

Obviously. I think there are militaries in Southern Africa that would desire to have the size of our defence budget, but – and this is an important but – then many, many unpopular decisions will need to be made regarding the restructuring of the military, regarding technology and regarding the personnel situation. I don’t know if our strategic decision-makers have the gravitas to make those difficult decisions that are necessary to align our military with the budget and with the work they need to do. I doubt it.

Where’s the knot? Why doesn’t it happen?

The problem lies in an interaction between unpopular political decisions that must be made, in other words political leadership, and the fact and problem that strong and effective military leadership is needed. If the political decision is made, very clear military leadership will need to be demonstrated. The essence of many of the problems we’re sitting with today is the lack of directional military leadership.

On the same theme, how is parliament doing with its oversight role, and how is defence minister Angie Motshekga doing?

Wilhelm Janse van Rensburg, the researcher for parliament’s two military portfolio committees, did a study clearly showing how parliament’s oversight role has diminished over the past 20 to 30 years, to the point where the executive authority, the minister and the president, together with the military, essentially wipe their backsides with it. They don’t really pay attention to parliament’s oversight; in fact, the military holds parliament in contempt.

It was interesting to see this week how the portfolio committee for defence reprimanded a general because he has never bothered to appear before the committee. Why doesn’t he appear there? Because the minister … well, let me not get into that.

The other important point to make is that the oversight role over the military, worldwide, has fundamentally changed in the past 40 to 50 years. It has changed to the extent that parliaments are no longer the only oversight mechanism that exist, because the role that social media, academics and the media have begun to play has become critically important … Look at how the general population is reacting on social media about the mess and debacle happening in the DRC. They don’t spare the rod when it comes to criticising the minister and the generals.

In 2012, a comprehensive defence review was done under then minister Lindiwe Sisulu, but nothing came of it. Is it time for something like that again?

Oh, I don’t even doubt it. The previous defence review was worthless because it was done in a budget-independent and threat-independent environment. If you ignore the budget and the threat when you do the review, or rather a new white paper on defence, which I think is actually needed, then that defence review isn’t worth the paper it’s written on. Then it’s like someone dreaming of buying a R4m Toyota Land Cruiser but they can only afford a Toyota Tazz.

We’ve been reading for decades how the integrated military consists of more officers than troops and that it’s a big problem. Is it still like that?

Well, it’s actually worse. Let’s first talk about the personnel situation. We’re sitting with a top-down problem: a mushroom-like military, with an enormously large corporate army in Pretoria. The Pretoria army is disproportionately large compared to the so-called field army. Instead of a triangle hierarchy, we actually now have an inverted triangle.

There’s a history. The apartheid military was structured with a large permanent force headquarters that also had the conscription operational footprint and the reserve force footprint, which was exponentially larger than just the permanent force headquarters. Then in 1994, they built on that permanent force headquarters, but they moved towards what was supposed to be a small professional army, and it didn’t happen.

The personnel management of any military works on the principle of “up or out”. It means that if a person isn’t promoted after four to six years in a rank, then the military is essentially giving them the message that they should leave the system. Our people simply weren’t managed out of the system. So there are troops, corporals, you name them, who were never promoted, who are 50, 60 years old, which is retirement age, but they are troops.

Are there any parts of the military that are still relatively functional, even exceptional?

Oh yes, there are certainly pockets of excellence, I don’t even doubt that. The special forces is one of them and there are still some infantry units that are very good.

However, one of the big problems is the overloaded top management and the skills levels of many of the so-called top people. The other problem is that it’s as if we no longer understand that the soldier with the weapon in hand is the essence of a strong military. Where is that soldier’s training and his equipment and his discipline?

I think we’ve driven too many soft issues since 1994, and here I’m specifically talking about the integration process of the military. We’ve taken our eye off the ball. They organise all sorts of conferences. The soft issues have become more important than the soldier, and when a military reaches that point where the soldier is not the essence, then we’re in big trouble.

Regarding equipment, is it a case that we have the wrong equipment, or is it outdated?

I think our military still has good equipment, but it hasn’t been maintained since 1994 due to the defence budget. That’s one side of the truth. There is also equipment that must be replaced. Let me give you an example: our Samil fleet of logistical vehicles, of trucks, was put into use in 1981 or 1982. They’ve been through a bush war!

There aren’t cars in the public sector that are 50 years old that are used every day, and not vehicles that have been through a bush war. So it’s simple things like a logistical fleet that needs to be replaced.

As for the air force, what do we need there?

The air force won’t like what I’m saying, but the biggest mistake we made with the purchase of aircraft was buying fighter jets. I say sell the Gripens and buy a strategic airlift service. We need cargo planes and we need attack helicopters.

We’ve seen in Ukraine how commercial technology, which is relatively cheap, can be used very effectively. The air weapon has increasingly shifted from manned fighter aircraft to unmanned drones. The air weapon is still the air weapon, but there has been a fundamental change from manned, large, expensive aircraft to unmanned, cheap aircraft. An effective drone can cost as little as R25,000.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.