Vuyisile Mshudulu. It’s a name that has cropped up repeatedly in Currency’s discussions with insiders into the state of collapse at the Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG).

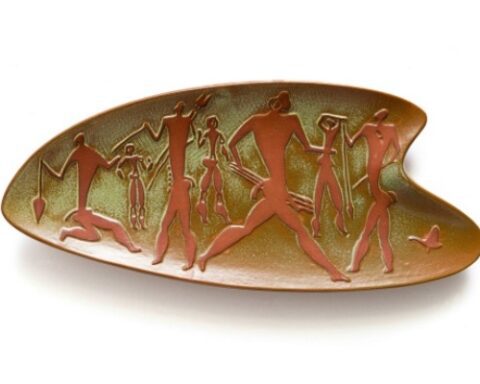

As Currency has reported, the JAG is falling to ruin; the building is decrepit, artworks are damaged, exhibition halls stand empty and just 1% of the 9,000 paintings and artefacts in the gallery’s collection are on display.

Joburg’s collection – worth hundreds of millions of rand – is owned by the people of Joburg, yet the authorities are failing in their mandate to preserve this corner of the city’s heritage. This is despite a plethora of influential players involved: the city itself, the art gallery committee, the Friends of the JAG (FoJ), the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation (JHF), and a key former donor, the Anglo American Johannesburg Centenary Trust .

In part, the state of the gallery is the result of the chaos that surrounds the collection – and city staff who have exploited this.

Chief of these, say a host of sources, is Mshudulu, the head of the local department of arts, culture and heritage, which has oversight of the gallery. He has steadfastly refused to answer any questions sent to him by Currency, by email and phone.

After his initial response to Currency – telling us to set up an interview via the city’s spokesperson, Nthatisi Modingoane, who failed to do this – Currency sent a further series of questions that Mshudulu read, but did not respond to.

Yet every source tells Currency he is the person at the centre of the JAG debacle.

Two weeks ago, the DA’s shadow MMC of community development, Lyrics Mazibuko, and MP Andrew de Blocq conducted an oversight visit to the gallery following the stories published by Currency and Daily Maverick, but were denied access by Mshudulu.

“The chief curator decided to call him, saying: ‘Lyrics is here, please assist me in terms of making a decision whether I should allow him into the building’ when we were already there,” Mazibuko tells Currency.

Mshudulu, he says, refused to allow curator Khwezi Gule to open the gallery’s coffee shop and basement, where much of its art is stored.

“Conveniently they were only able to show us the remaining artwork that’s still on display. Mshudulu said we should speak to the MMC for community development, but we don’t report to them; the MMC reports to us – so why should we ask his permission to hold him to account?” says Mazibuko.

He argues that in blocking the delegation, the gallery acted against a resolution that the city’s committee for community development passed to investigate what is happening at the art gallery.

“I have requested the progress report on JAG; what is the plan, what art has been destroyed, how many artefacts have been removed, and where they are. Our role is to compare what has been given to us and what is the situation on the ground, and they did not give us that opportunity to make that comparison,” says Mazibuko.

‘Placeholders for a future plan’

While the FoJ and the JHF have appealed to the mayor’s office to move the gallery’s valuable collection, Mshudulu appears to have outsize influence in the discussions.

To date, it appears he has not used this influence to address the crisis.

According to the FoJ, a meeting with Mshudulu last month, which followed a meeting with the mayor, “yielded vague outcomes”.

“There was no timeline or details, just opaque notions presented as bullet points that seemed like placeholders for a future plan,” says FoJ member Eben Keun.

Similarly, Keun says, the vague talk of some kind of tender process to address the crisis at the gallery, governed by the City of Johannesburg, “raises concerns”.

“The city’s history of botched renovations by unqualified appointees over the past decade does not inspire confidence,” says Keun. “And there was no suggestion of a collaborative approach involving the people of Joburg, the rightful owners of this collection, based on the deed of donation.”

Dada Morero, Joburg’s new mayor, has, however, now approached local group Jozi My Jozi (JMJ) to oversee the JAG project, says the JHF’s David Fleminger.

“Our lawyers are trying to set up a meeting with JMJ this year to discuss what operational role JMJ will play in the process and to determine if/how we can be productively involved,” says Fleminger.

If that doesn’t work, says Fleminger, the organisations will then decide whether to pursue further legal action.

“We are not opposed to working with JMJ – the goal remains getting the entire collection to a place of safety and we will support any efforts to get that done as soon as possible. However, we have some questions about whether the JMJ plan includes the continued involvement of Vuyisile [Mshudulu] and other city structures,” he said.

Fleminger says that as a condition of its participation, the organisation would also require the full inventory of the catalogue and “unrestricted access to the building”.

This is a fundamental sticking point: the city, for no reason it has properly explained to anyone, has refused to disclose the inventory of a gallery that is owned by the public — not the officials who are keeping it secret.

When Currency asked, this request was ignored. But this is not a story that will end well for those opting to hide what is happening behind the gallery walls.

‘Bunkum’

Mshudulu’s influence in the city has grown steadily since he was appointed by former member of the mayoral committee (MMC) for community development Nonhlanhla Sifumba in 2017.

He is central to a contested loan of artworks – the most important in the gallery’s collection – that have been touring Italy and Hungary since 2019, and which have now headed to South Korea.

His international ambitions appear to be encapsulated in a biography circulated on Ars Electronica, an art blog linked to the annual Austrian Ars Electronica art festival held in Linz, in which he seemingly participated.

According to that write-up, Mshudulu is said to be an art “historian, writer and curator who has worked in Australia, Europe and America”.

It continues: “He was the curator of the collections at the Getty Centre in Los Angeles from 1994 to 2004. He was the artistic director and curator of the 2006 Sydney Biennale and a senior research associate at the Center for Intercultural Research, Australian National University (ANU).”

That biography says he has “taught at several universities and has published and presented many works”.

Curiously, Mshudulu’s LinkedIn profile and a CV that Currency obtained from the City of Joburg bear no resemblance to the illustrious career described above.

According to his CV, he obtained a bachelor’s degree in development studies at Unisa between 2010 and 2013, before which he attended the Northern Cape Technical College between 1999 and 2001 – at a time when the other biography says he was curating collections at the Getty Museum in LA.

His own employment history meanwhile starts in 2001, as a “craft development officer” in the department of sport, arts and culture, in Kimberley. By 2008 he was an “international market access co-ordinator”.

When Currency asked a source in the Australian embassy (embassy staff aren’t authorised to speak on the record) about Mshudulu’s involvement in the 2006 Sydney Biennale, the reply was emphatic: “It’s bunkum.”

The 2006 Biennale annual report does not list Mshudulu as the artistic director and curator (that was, in fact, a Charles Merewether). And the embassy source says there is no record of a centre for intercultural research at the ANU at all.

Again, Mshudulu’s own CV says that in 2012 he was the programmes manager at the Bokone Bophirima Craft and Design Institute in the North West until, in 2014, he was made a deputy director at the department of trade and industry. In August 2017 he was appointed director of arts, culture and heritage at the City of Joburg.

Currency specifically asked Mshudulu who wrote the CV; he read our message, but did not reply.

A controversial character

At JAG, Mshudulu’s tenure has been marked by increasing strife.

Insiders, who work at other cultural institutions in Joburg say that when Anglo American in 2022 tentatively offered the use of its previous head office, 44 Main Street, as a temporary refuge for the artworks stuck in the decaying Joubert Street gallery, it was Mshudulu who nixed this.

Yet his remit, apparently, is vast – including the appointment of staff at the JAG, even though chief curator Gule is nominally in charge.

“Vuyisile should not be sitting in those [employment] meetings because we’ve already got a manager who these people are going to report to,” says one source, who describes an exodus of experienced gallery staff, and the loss of decades of institutional knowledge under Mshudulu.

“Since Mshudulu joined, to date, they’ve been talking about how they are going to restore JAG. And we are getting nowhere.”

The haze of secrecy and obfuscation over what was once the southern hemisphere’s most valuable art collection all seems to centre on Mshudulu – yet he is not saying anything to anyone, evidently hoping to ride out the storm.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.