Finance minister Enoch Godongwana’s October mini-budget was presented the day before Diwali and the day before Halloween – which is appropriate because it can be read as a horror story. Or, alternatively, as the spiritual victory of light over darkness.

Many government budgets have the same propensity – they are so huge and complex that they tend to be informed by the prerequisites of the observer. But this particular medium-term budget policy statement (MTBPS) presentation was more than normally complicated.

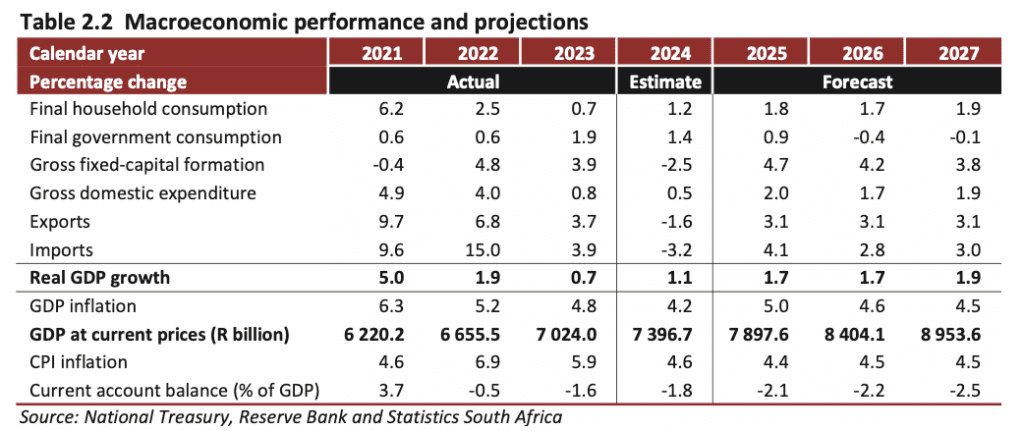

For those with a horror story inclination, almost every major factual indicator presented in the mini-budget was bad: GDP growth was paired back slightly; tax income was lower; the deficit was higher; the peak of the debt curve was increased.

Initially, the markets were a little taken aback by these numbers, but by the end of the day, other pressures had taken over.

It’s not just the new data; the old data is pretty scary too, and Godongwana spoke very plainly about the level of national debt. “Debt has risen too fast and is too high,” he said.

Plain, but the numbers now are positively Chucky. Government debt will reach more than R6.05-trillion, or 75.5% GDP, in 2025/26. It will be the largest component of spending precisely because spending is rising faster than economic growth. Debt-service costs will reach R388.9bn in the current financial year.

But for those with a Diwali disposition, in the mighty battle between Dharma (structural change) over Adharma (a debt spiral), Godongwana outlined a whole host of measures to boost growth without increasing government expenditure.

Some of these we know about; some are new and complicated. But all are aimed at getting the private sector involved in the economy. The ideas are somewhat similar to the renewable energy independent power producer procurement programme, and a whole list of big projects was outlined. You can feel the urgency: Treasury’s budget facility for infrastructure is now going to finalise projects every quarter, not annually as before.

A ‘change in emphasis’

Economic analysis of the mini-budget reflects the same duality. Capital Economics chief emerging markets economist William Jackson noticed a “major change in the emphasis” of the MTBPS. “Whereas the budget presented in February of this year talked of the need to strike a ‘balance’ between curbing fiscal risks and supporting the economy, the MTBPS was unambiguously presented as setting out a ‘pro-growth agenda’,” he said. It focused heavily on recent progress, including alleviating energy shortages and reforming the visa system.

However, poorer fiscal projections mean government expenditure is expected to decline relative to GDP. In these circumstances, that’s encouraging given the scale of South Africa’s fiscal vulnerabilities, he wrote in a note to clients.

On the other hand, what it does mean is that ongoing fiscal austerity will make it harder for the government to see the pick-up in growth that it’s hoping for. “An improvement in growth will have to rely on structural reforms to raise human capital and investment from the private sector. Though there have been positive moves in this direction and easing load-shedding will help, the fruits of reform will take a long time to materialise.”

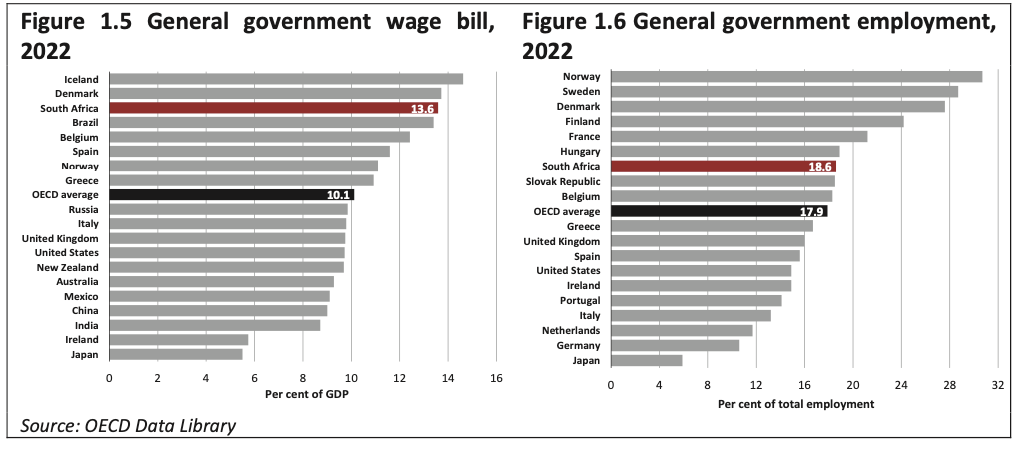

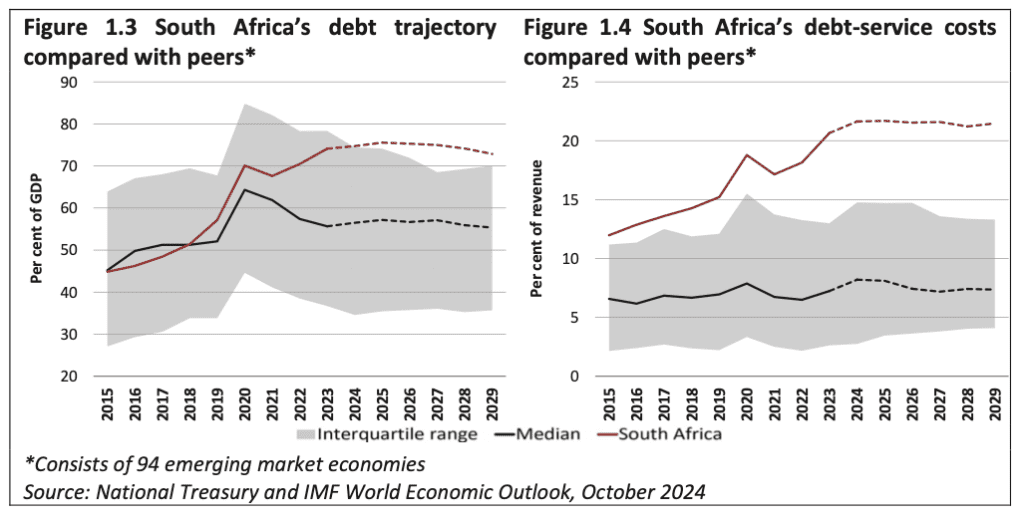

It’s well known but worth repeating that South Africa is in this position because, over the past decade and a half, the government has meaningfully slipped off the rails. In the Budget Review, the Treasury highlighted the problems very graphically, using a comparative approach.

Take a look at this graph: South Africa’s general government wage bill is just under 40% higher than the average Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development level as a proportion of GDP, and third highest of the group. The comparison explains why Godongwana has put aside R11bn to encourage early retirement in the civil service. (See Currency’s story on that here.)

Or this one, on the Chucky-esque debt problem. South African debt is not bad in itself, but it is way out of kilter compared to its peers, and the cost of debt has just been exploding, almost doubling over the past decade.

‘Too early to say’

So how should investors react? Oddly enough, just before the mini-budget, the JSE was holding its annual SA Tomorrow conference in New York, which brings together a host of South Africa’s leading companies with a senior government delegation.

JSE CEO Leila Fourie said in an interview that the atmosphere at the conference was a marked improvement on last year, and she got the sense that a rerating was distinctly possible.

But it would be a rerating from a low point. “Over the past four years we’ve seen a contraction in South Africa’s relevance globally, where South Africa’s weighting in the MSCI emerging market index has contracted to what is now about 3%. Even after the contraction, investors were underweight the index, so they were investing less than 3%,” she said.

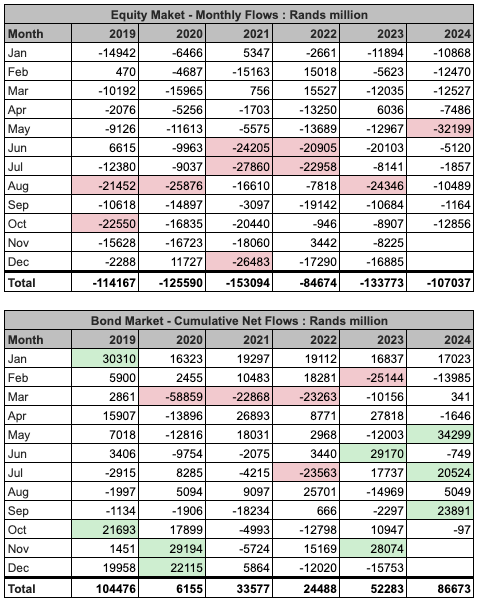

But the JSE has been seeing more interest in South Africa recently, particularly in the bond market. “We are starting to see certain investors indicating that they’re going to take a more balanced position in the index. And some may call the bottom and even invest overweight. So there is a growing momentum and positive expectations on the government delivering on their promises,” Fourie said.

“All of the controllables within South Africa are looking more positive than negative but I’m very cautious at this stage. It’s too early to say where we’re going to land”.

The JSE’s investment numbers do show some slight improvement in inflows but on the equity market, the truth is that the net number is still negative. Inflows into the bond market on the other hand are looking much better.

The real lessons of the mini-budget are threefold. First, the restoration of fairly constant electricity is not sufficient to bring about an economic recovery on its own. There was no load-shedding during the 2024 winter period, compared to 153 days of load-shedding in the 2023 winter. The change was sufficient to boost corporate profitability, but not sufficient to boost personal tax or VAT income.

Second, government’s new enthusiasm for public-private partnerships is in fact not a choice; it’s being forced on the government because the other alternative, increasing browning, has been exhausted. And third, the time period required for significant economic change is probably longer than most estimates suggested up util now. Structural changes are what is required, and those take time.

Diwali is marked with fireworks and lights in order to overcome Adharma. South Africa clearly needs more than a distant light – it needs the fireworks.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.