South African Reserve Bank (SARB) governor Lesetja Kganyago is proposing to lower the inflation target in South Africa. Yet there is little independent research to support such policy reform, let alone a SARB policy document to interrogate.

South Africa’s inflation target range of 3%-6% or, more specifically, the 4.5% midpoint, is higher than many other emerging-market economies, so there is an argument to be made for transitioning to a lower target. But there are many unanswered questions about the definition of the target that would be appropriate, given South Africa’s economic context.

High structural inflation has weakened the competitiveness of South Africa’s exporters and the buying power of the rand. This has contributed to South Africa becoming a high-cost, low-productivity economy. A lower inflation target would help in this respect, but there is a raft of structural and political factors that have contributed to the decline in South Africa’s cost competitiveness and long-term increase in relative prices.

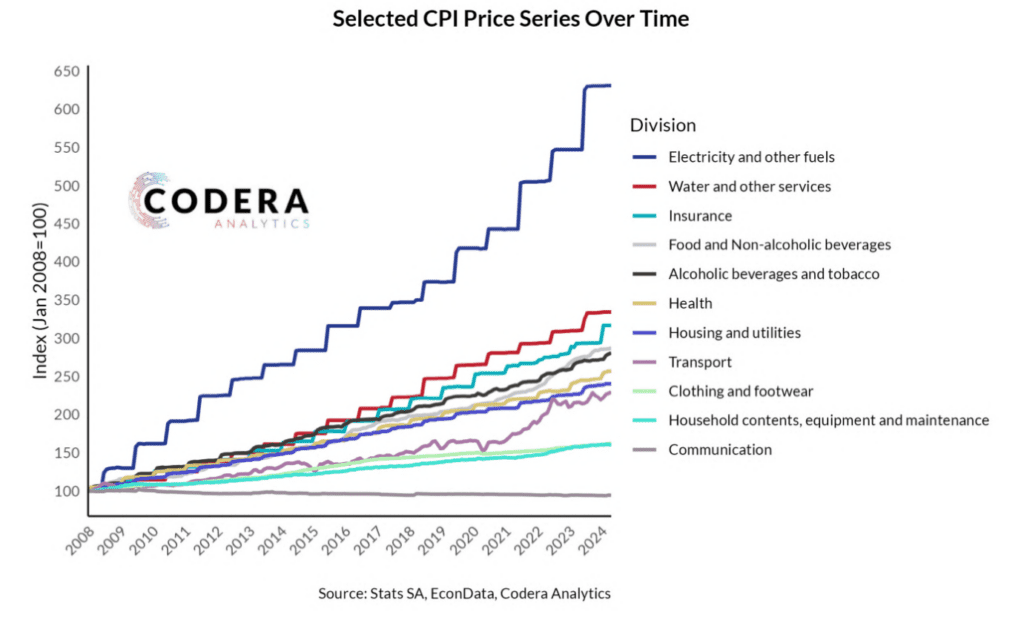

A key challenge for the SARB is that several government-determined inflation components, including fuel, electricity and water, have persistently risen well above the upper limit of the inflation target range. The SARB cannot directly influence prices in these areas, so maintaining high interest rates in response to such pressures places a burden on more flexible parts of the economy. Achieving structurally lower inflation will require a sustained reduction in these government-driven cost pressures.

In a recent speech, Kganyago suggested that disinflation costs in South Africa have generally been low. Our estimates, which are consistent with recent estimates from the International Monetary Fund, suggest that the costs of shifting to a lower inflation target might be higher than those implied by the governor.

If the costs of disinflation are high and the SARB were to struggle to achieve a lower inflation target, it would hurt the reputation of the bank. Worse still, an absence of supportive fiscal policy could undermine the extent to which a more ambitious target reduces borrowing costs in the economy.

Lowering the target without buy-in from the government would raise the adjustment cost for private sector firms and erode the SARB’s hard-won credibility.

If the inflation target is to be revised, the rationale behind a target change will need to be clearly and publicly articulated. To build trust with households and price-setters, evidence of long-term benefits that make it worth bearing any short-term costs should be presented.

Complementary policies that support the SARB’s disinflation efforts should also be outlined. Such policies could include structural reforms that reduce government-related inflation, promote the responsiveness of inflation to monetary policy and public commitments to the new target by organs of the state and labour unions.

Another gap in the debate about the inflation target is how it should be measured. Several considerations matter for how it should be defined. These relate, for example, to selecting a price index that is relevant to the experience of firms and households, or the types of shocks the economy is exposed to.

In South Africa’s case, inflation is very sensitive to imported inflation and supply-side shocks, including the exchange rate and weather. There is very little academic or policy research that addresses these issues in a South African context.

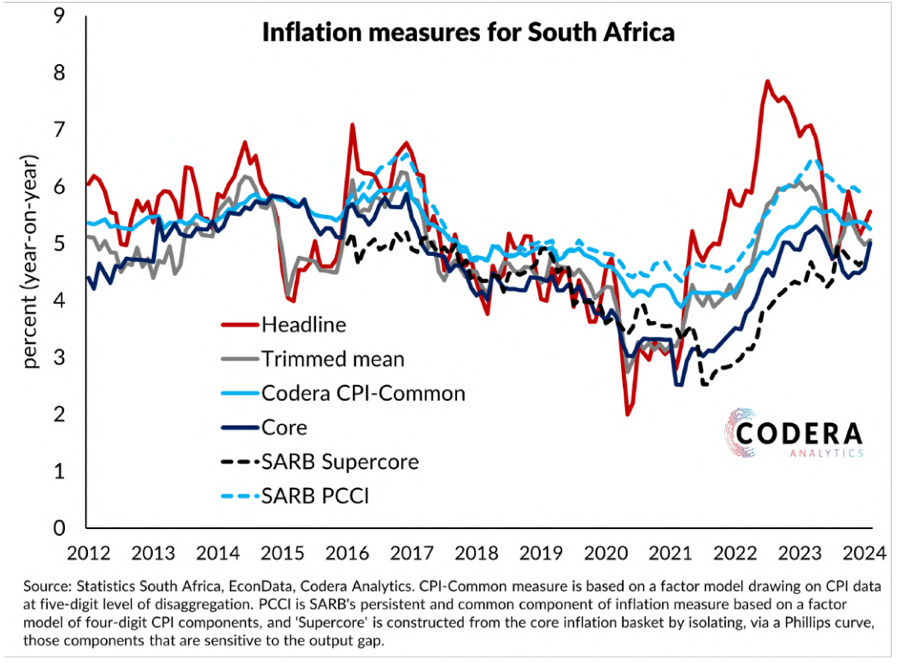

The measures presently used by policymakers to assess inflation dynamics do not sufficiently describe the nature of structural inflation in South Africa. There are biases and uncertainties in the statistics monitored by the central bank that affect judgments around underlying inflation pressure.

These affect assessments of the appropriateness of policy settings, given the importance of supply shocks in the determination of inflation in South Africa. This also creates a communication challenge for the SARB, given differences in the inflation experienced by different households and firms.

Even though inflation has recently fallen towards the bottom end of the SARB’s target range, measures of trend inflation have been stubbornly above the midpoint of the inflation target, and there is a high degree of inflation dispersion across price categories.

Our estimates of underlying inflation pressure also suggest that there has been more broad-based inflation pressure since the pandemic than implied by the core measure that excludes some volatile components such as food and fuel prices that the SARB focuses on in its monetary policy statements.

New measures

To be able to judge the rate of structural inflation, and when an opportune time would be for a reduction in the inflation target, the SARB needs new measures of underlying inflation.

To understand the impact its policies will have on the economy, the SARB must use frameworks for interpreting the economic drivers of underlying inflation pressures on an ongoing basis to support its policy credibility.

Despite expectations near the mid-point of the current target, monetary policy will need to stay tighter than otherwise to lower inflation expectations further and anchor inflation to a lower level over the medium term.

The duration of a more restrictive policy stance would depend on whether households and businesses believe the SARB is fully committed to bringing inflation down to the lower target and keeping it there.

Achieving this without raising interest rates beyond current projections would require a strong government commitment to tackling the root causes of structural inflation. This includes improving efficiency in electricity production, curbing high administered price inflation, and ensuring public wage increases align with productivity growth.

Political co-ordination, including a social compact between the government, the SARB, state-owned enterprises, relevant regulators and labour unions, would bolster the credibility of any central bank programme to reduce trend inflation permanently. An inflation targeting compact is unlikely without clear articulation of the benefits of a lower target and what is required to counterbalance the short-term costs of reducing inflation.

Dr Steenkamp is CEO of Codera Analytics and a research fellow with the economics department at Stellenbosch University. You can access Codera’s policy paper on gaps in the South African inflation targeting debate by clicking here.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.