In a packed exhibition hall last week, De Beers CEO Al Cook and Botswana’s new mining minister Bogolo Kenewendo laid out a plan to launch a new “natural diamond dream” into a world now awash with lab-grown stones.

It’s an ambitious scheme, not least because diamond prices have plunged not only due to the sudden ubiquity of lab-grown diamonds, but also due to the frailty of consumers in China who, until now, have hoovered up large swathes of diamond jewellery.

The grim truth is evident from the correlation between the Zimnisky global rough diamond price index, which shows prices dropping 22.6% over a decade, and the fact that lab-grown diamonds accounted for 14.3% of all diamond sales by 2023 – a share that nearly doubled in three years.

For De Beers, the world’s largest diamond producer 85% owned by JSE-listed Anglo American and 15% by Botswana’s government, reviving diamonds is a job for the marketing gurus.

“People are recognising that a synthetic diamond grown in a microwave in China in three weeks is not the same as something developed in the ground over a billion years under the soils of Africa,” said Cook at the Cape Town Mining Indaba.

It is an optimistic take given that, as McKinsey wrote last year, lab-grown diamonds have “essentially the same physical properties and undergo the same cutting and polishing, and distribution steps as natural diamonds”.

But Cook argued that the distinction between natural and synthetic diamonds is very clear in the consumer mind, citing the fact that you can now get about 20 synthetic diamonds for the price of one natural diamond.

Kenewendo agrees, adding that her government is “prepared to go into the global markets [to] change the story”, trumpeting the superiority and provenance of natural diamonds over their lab-grown cousins.

But can juiced-up marketing and a better narrative alone revive the diamond market?

That McKinsey study, for instance, outlined the poor fundamentals, including how natural diamond production is set to grow at between 1% and 2% until 2027 – less than half of previous estimates.

“After surging during the pandemic, diamond prices have reversed to multiyear lows,” it says. “Where the industry goes from here depends on how companies respond to these changes.”

But Cook is betting on the fact that De Beers has successfully revived diamond prices once before through arguably the savviest marketing intervention in history.

Romancing the stone

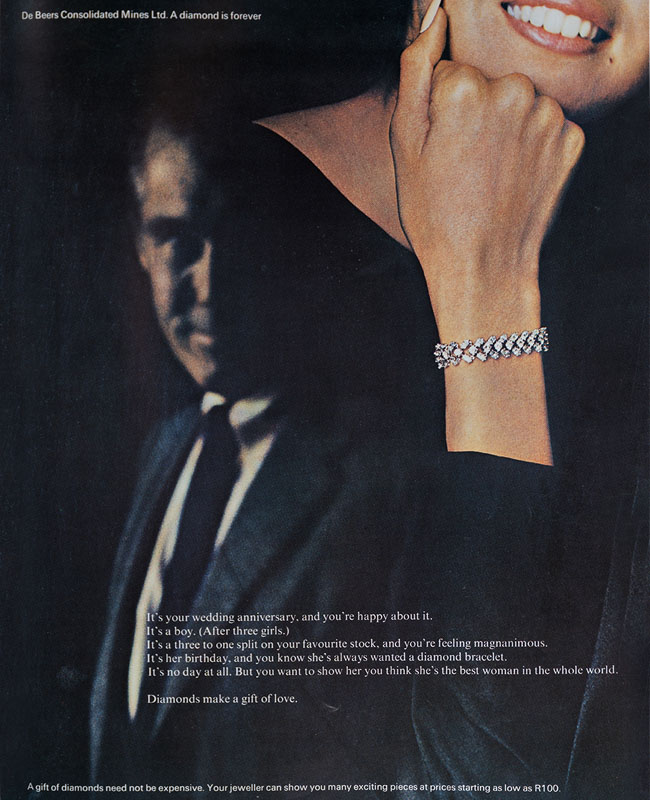

In 1938, Harry Oppenheimer, son of Anglo American founder Ernest, and Gerold Lauck, who headed New York advertising agency NW Ayer & Son, devised a plan to arrest a slide in diamond prices, which had halved over the previous 20 years as people bought increasingly smaller stones for engagement rings.

“Oppenheimer hoped that an ad campaign could persuade middle-class Americans not only that diamonds were integral to courtship, but that the purchase of more diamonds at higher prices was a direct expression of love,” wrote Susan Falls, in her 2014 book, Clarity, Cut, and Culture: The Many Meanings of Diamonds.

It worked, and within three years, sales had spiked 55%.

De Beers’ crowning glory came in 1947, when NW Ayer copyrighter Frances Gerety came up with the slogan “A Diamond is Forever” to underpin the company’s campaign.

“Even though diamonds can in fact be shattered, chipped, discoloured or incinerated to ash, the concept of eternity perfectly captured the magical qualities that the advertising agency wanted to attribute to diamonds,” said a 1982 article in The Atlantic.

The slogan was so stunningly successful that it was dubbed the “most effective marketing campaign of the 20th century” by the prestigious Advertising Age magazine. Diamonds soon became routine product placements in movies, while adverts asking: “How Can Two Months’ Salary Last a Lifetime?” adorned Time magazine.

Then, in 2010, De Beers made a strategic marketing blunder: it stopped marketing diamonds as a category, and began marketing its own brands instead.

Cook explains: “From the 1930s to 2010, a period of 70 or 75 years, De Beers marketed diamonds – a ‘diamond is forever’, a ‘tennis bracelet’, an ‘eternity ring’. From 2010 onwards, we marketed brands – De Beers Jewellers and Forevermark.”

The result was that diamonds lost their sparkle.

“If you don’t market diamonds for 10 or 15 years, guess what happens? Desire for them decreases,” said Cook. This meant, for instance, that those people getting married in 2025 will never have seen those adverts.

Cook aims to go back to what made De Beers successful: marketing diamonds as a category, rather than his own company.

Dancing on TikTok

It’s a rational plan. But much has changed since 1947 that would make it far harder to replicate that marketing success today. Not least of which is that, at the time, De Beers controlled an estimated 85% of the market, whereas today it is nearer 35%.

And, perhaps more to the point, lab-grown alternatives were not around in 1947.

In an increasingly price-conscious world, convincing people to shell out more for a natural diamond than its physically comparable lab-grown equivalent is a hard sell.

The Knot, a wedding vendor marketplace, surveyed 10,000 couples who got married in 2023, and found that 46% of all engagement rings were made of lab-grown diamonds – “which is nearly four times as high as it was in 2019”.

To counter this, Cook said De Beers’ new marketing partnership, launched last week with the Botswana government, will go hard at punting the story of natural diamonds, while shifting the ideological battle from traditional avenues like magazines and films, to social media.

“What really matters is relevant marketing targeted at the right people,” he said. “De Beers does need to dance for its dinner on TikTok.”

As for telling a story, he said the diamond industry needs to embrace the tactics of coffee suppliers, who are quick to speak of how any particular blend might come from Ethiopia or Jamaica. Similarly, shirts bear labels designating them as Egyptian cotton.

“Yet when I go to a jeweller in the US to buy one of the most important and expensive purchases in my life, I ask: ‘Where is that diamond from?’ And they say, ‘I don’t know’,” he said.

Cook isn’t wrong that this is one of the clouds over the natural diamond industry. Suspicions over whether any stone is a “blood diamond”, mined in a country with lax controls like Zimbabwe, where the proceeds are used to prop up dictators, were meant to be addressed by the 2003 Kimberley Process, through which diamonds were certified as being “conflict free”. But this didn’t allow buyers to trace individual diamonds.

Now, for the first time, a diamond’s path from mine to finger can be traced.

As Cook put it: “If we are going to tell a story of the good that diamonds do – that they create so much social value in places like Botswana – we need to be able to tell people their diamonds are from Botswana.”

Another strategic shift is that De Beers has put a stop to producing in-house lab-grown diamonds for jewellery. This would seem to be a no-brainer, and it allows Cook to now claim that “we are a natural diamond company”.

Still a girl’s best friend

But can diamond prices really be shifted by smart marketing alone? Is today’s generation not far too sceptical to buy another “natural diamonds are forever” schpiel?

McKinsey argues that natural diamond producers, as well as those who produce lab-grown alternatives, “have the chance to benefit from consumer demand, if they can play into their differentiating factors, whether rarity, price, or volume”.

And it’s positive for De Beers that consumers haven’t fallout out of love, either with diamonds, or each other.

The Natural Diamond Council surveyed 5,000 people during Covid and found that women and millennials – those aged between 25 and 39 – still rated diamond jewellery as among the top two most desirable luxury items, alongside high-end vacations.

“There will be continuing interest by millennials and Generation Z [ages 18 to 24] in natural diamond jewellery, but social media will play an increasing role in inspiring their actions,” it said. Perhaps we really will see De Beers dancing for its supper on TikTok.

The problem remains, however, that marketing alone won’t cure the weakness in the Chinese consumer market – a vital point, since Chinese jewellery buyers are more likely to buy natural diamonds than the lab grown variety.

Duncan Wanblad, CEO of Anglo American, said on the fringes of the Mining Indaba last week that China remains the “real challenge” for diamonds. “We’re seeing some nice green shoots in the US, India looks really positive, but neither of them are really strong enough to replace the demand that came from China,” he said.

If China recovers, half of De Beers’ job will have been done.

But in a sense, Cook has no choice but to believe his company has the potential to shift the market. On his side is the realisation that De Beers has done it once before.

“De Beers did so much to create the allure and desire for diamonds in the 20th century, and it’s not my job to sit back and say, ‘the market will take care of itself’,” he said. “What we need to redo is restart category marketing in a way we haven’t done in 15 years and create a new diamond dream,” he said.

This coverage of the Mining Indaba was brought to you in association with Northam Platinum.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.