The Competition Tribunal’s decision to block cellphone giant Vodacom’s bid to buy Vumatel owner Maziv has sparked a vigorous debate about whether the decision is a brave attempt at securing a competitive market or a poke in the eye for township internet. Or both.

The tribunal hasn’t yet given its reasons, opening a cavity that has been quickly filled by wrangling over whether the decision will effectively constrict South Africa’s already miserable data usage in townships.

What should have happened, had the deal been approved, was for Maziv to use the proceeds of the Vodacom investment to turbocharge the expansion of its fibre networks.

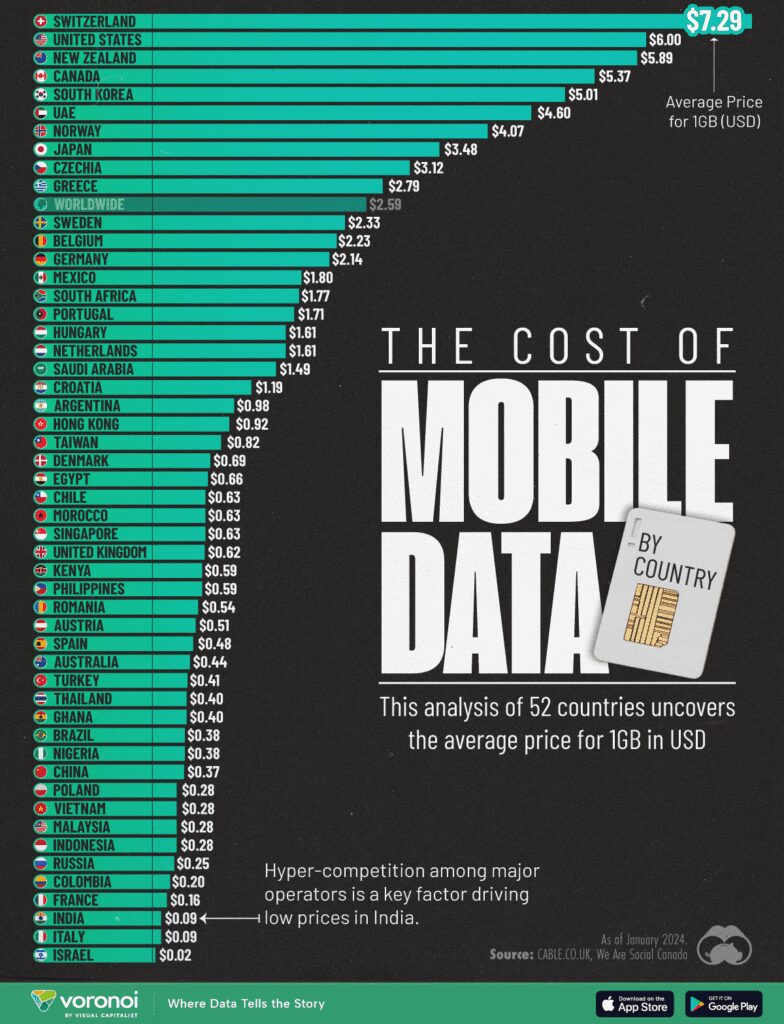

You can see why disagreements on the issue are intense: it’s difficult to imagine a more crucial or immediate digital divide issue. The essential problem is that though there is digital access in South Africa’s poorer areas, it’s pretty expensive by international standards and consequently is poorly utilised.

South Africa’s 2022 census revealed that households with internet access increased strongly over the previous decade, rising from 35% to 79%. But this is a bit of a misnomer because the census found that home internet access had only increased from 8.6% in 2011 to 12.3% in 2022.

The rest happens on cellphones, and amounts to average usage of about 4GB per month, at least for Vodacom users as reported by MyBroadband. The average download speed on the cell network in South Afridca is 70Mbps, which Omni Calculator suggests would download 4GB in 7.5 minutes. The dream of poor kids making use of the extensive facilities on the internet to help with their homework is clearly not being realised.

Compare that to internet usage in the US, for example, where in the second quarter of 2023, the average US household consumed more than 533GB of data per month.

Still, data usage is increasing and getting cheaper in South Africa. The census reported that just over 60% of households did actually record using the internet in 2022, and that is a massive increase from the mere 16.3% that used it in 2011. Increasingly, the issue is not access; it’s the price of access, and the massive cost per gigabyte improvement takes place not with mobile connectivity but with direct fibre connectivity.

Of course, the cellphone companies know this, and need to protect their growing data revenue, or at least participate in fibre provision so they get a slice of the market. You can see why Vodacom’s bid for Maziv attracted so much scrutiny.

Pooling resources

The main argument in favour of the merger is simply that the capital required to effect the rollout of fibre is, well, massive – though once the fibre lines are there they go for decades.

Remgro-owned Maziv, which in turn owns Dark Fibre Africa (DFA), for example holds R25bn in debt on its books, refinanced by a group of lenders led by Standard Bank last year. That sounds like a lot, but the company is now showing good margins: as of end-March 2024, revenue was R6.4bn and operating profit R2bn.

Since inception, Vumatel has connected more than 2-million households and has a network of more than 50,000km of fibre. Add to that DFA’s 15,000km. Its main rival, Telkom’s Openserve, has grown the number of homes passed with its own fibre broadband infrastructure to just over 1-million homes.

At the tribunal hearing, Dobek Pater, MD of Africa Analysis, was reported by TechCentral to have said: “If you look at countries similar to South Africa, we need large organisations with the ability to access lots of money and have the economies of scale to remain profitable, while at the same time providing affordable services to consumers.

“The deal would be positive in that it would create a larger entity able to pool massive resources and take advantage of synergies within the group.”

Other telecom experts agreed.

The actual deal would involve Vodacom paying Maziv R6bn in cash, after which Vodacom would move its fibre assets (valued at R4.2bn) into the company for a 30% stake, which could be increased in time to 40%.

The tribunal’s decision is especially shocking given the number of concessions that Vodacom had offered – which it and Maziv thought would swing the deal.

These included investing at least R10bn over a five-year period, predominantly in low-income areas, connecting a million new homes, providing high-speed internet to more than 600 schools and police stations at no cost. The concessions were so extensive that the department of trade, industry and competition actually came out in support.

No wonder Vodacom Group CEO Shameel Joosub said he was “deeply surprised and disappointed by the tribunal’s decision”.

“South Africa desperately needs additional significant investment, especially in digital infrastructure in lower income areas. Our investment of up to R14bn would have changed millions of lives and created thousands of jobs.”

Fair price

However, this view has been challenged by Tim Genders, the chair of the Wireless Access Providers’ Association (WAPA).

“This decision is in the interest of consumers getting a fair price for their broadband internet connection. Many WAPA registered companies are rolling out into lower-income areas across South Africa. They are making a financial success of it. They deploy pay-as-you-go billing models for internet access and connect to local entrepreneurs for reselling,” he says.

“The message that the blocking of the Vodacom-Maziv deal is a setback for the entire industry is complete nonsense. It is only a setback for the companies involved in the deal. WAPA member companies have successfully negotiated local and international investments to connect homes in South Africa.”

Genders is especially critical of the debt associated with Maziv’s expansion. Simplistically, Maziv’s debt pile of more than R20bn, plus the 2-million homes it has passed with fibre and the 1-million connected “equates to R10,000 debt incurred per home passed or R20,000 per home connected. WAPA members are connecting homes at a cost of R5,000 with fibre and R4,000 per home with fixed wireless access,” he notes.

“It is hard to make sense of the deal in any other way than an attempt to lock out competition. In which case the Competition Commission got it right to block it,” he says.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.