Donald Trump is complicating life for central bankers from Washington to Pretoria. He has forced Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell, Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey and now Lesetja Kganyago to steer through a fog of uncertainty – with far less room to cut rates.

And so, the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) governor held interest rates steady on Thursday due to concerns over the US president’s haphazard policies. It is the first pause since the SARB began cutting rates in September – though by only 25 basis points (bp) a time. Bailey halted a string of three consecutive cuts since August for the same reasons. The Fed this week stood pat for a second meeting, following three straight reductions in 2024.

Two of the six members of the SARB monetary policy committee (MPC) opposed the decision and wanted a 25bp cut. While the SARB’s decision to hold was in line with the median forecast of 21 economists surveyed by Bloomberg, seven of those had expected a cut.

One of those unhappy with the decision was Cy Jacobs, founder of 36One Asset Management, who believes the MPC missed a critical opportunity.

“The SARB is behind the curve,” he tells Currency. “We need to cut government spending and have a clear path to faster economic growth. Rate cuts would have helped.”

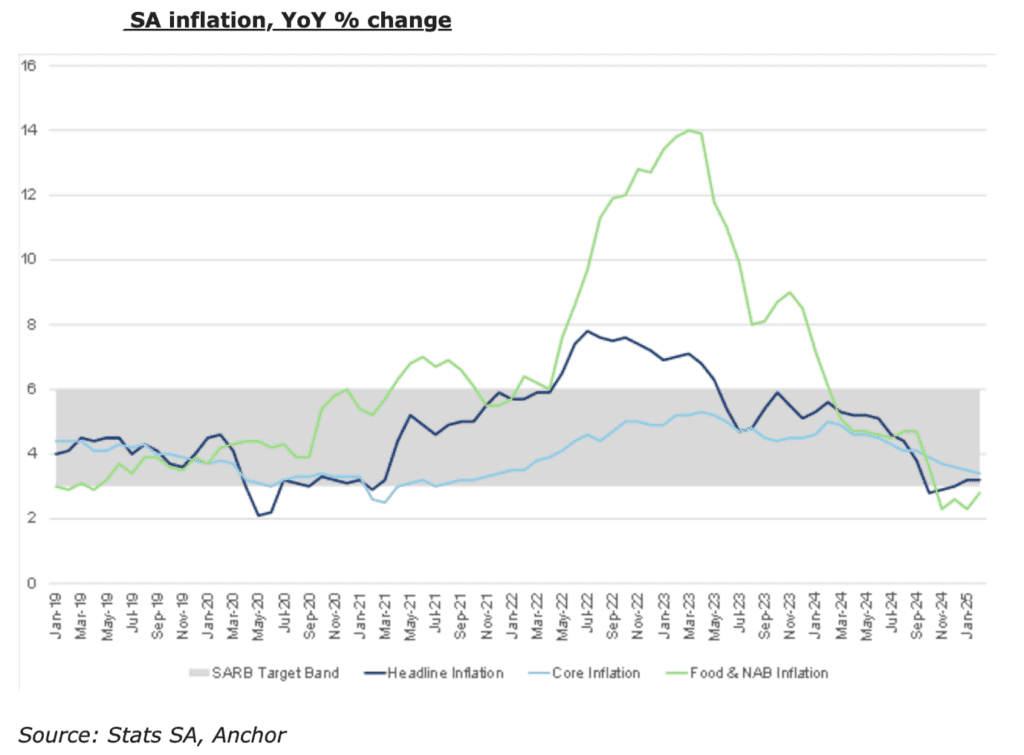

At the heart of the argument advanced by Jacobs and others is the stark gap between inflation and interest rates. Consumer inflation came in at 3.2% in February, once again undershooting analyst expectations. That leaves South Africa’s real interest rate – the nominal rate minus inflation – at 4.3%. It places the country in a cohort that includes Russia, Saudi Arabia, Kenya and Pakistan.

It also comes as the SARB revises its forecast for 2025 inflation down to 3.6%, from 3.9% in January. That improvement reflects a combination of factors: expectations of lower fuel prices, modest electricity tariff hikes granted to Eskom – and a 0.2 percentage point inflation impact from finance minister Enoch Godongwana’s proposed VAT hike of 0.5 percentage points for this year.

The downward trend is not new. In January, the SARB cut its November forecast of 4% inflation for 2025 – itself unchanged from September – and well down from a 4.6% projection published in March 2024. Though, to be fair, a lot can change in a year.

Compare this with Kenya, where inflation hit a five-month high in January – its fourth consecutive monthly increase – yet the central bank opted to cut rates for a fourth straight meeting in February to support growth and lending. Different strokes for different economies, but the principles remain.

Kganyago, meanwhile, remains unmoved. The SARB targets a 4.5% inflation midpoint but wants that to be lower – as low as 3%, in fact, if it gets National Treasury buy-in. That compares to Kenya’s broader 2.5% to 7.5% range.

The SARB governor has repeatedly argued that lower inflation is better for the poor, enhances economic stability, and provides long-term certainty for businesses. This, he says, encourages investment and, over time, creates the conditions for sustainably lower interest rates – a view consistent with the global consensus among inflation-targeting central banks.

People are getting poorer

To Jacobs, that logic doesn’t hold in an economy like South Africa’s – one that hasn’t grown by more than 1% a year in more than a decade. With population growth outpacing GDP, the average South African has been getting poorer each year.

“This economy is just going to continue to stagnate,” he says. “The only way we’re going to take care of the budget deficit is through faster growth.”

Indeed, the SARB now expects the economy to expand by just 1.7% in 2025, down slightly from a 1.8% forecast in January. Projections for 2026 and 2027 remain unchanged at 1.8% and 2%.

“After maintaining a balanced assessment for some time, the SARB now perceives the risks to growth as tilted to the downside,” says Casey Sprake, an economist at Anchor Capital.

Kganyago defended the MPC’s decision to hold, citing global uncertainty. South Africa, he said, cannot “disentangle” itself from the rest of the world, particularly in an environment where policy direction is increasingly erratic. Many analysts, policymakers and international publications have warned that the US president’s trade and other policies risk fuelling inflation – a trend increasingly referred to as “Trumpflation”.

“There had been so many moving parts that we had had to deal with,” Kganyago said during the MPC briefing. “Globally, we do not know where policy [will] end up. There are pronouncements across the Atlantic on both sides, and that becomes difficult to forecast.”

As usual – and not without justification – the governor reminded his audience of the SARB’s primary inflation-targeting mandate. He also shifted some responsibility for stimulating economic growth back to the government, citing the need to manage public debt, modernise network industries (rail, roads and ports), reduce administered prices (electricity, water, rail, ports and the like), and ensure that real wage growth reflects productivity gains.

Unfortunately for anyone with debt, and a previously firm belief that the SARB would slash rates this year, the Bank’s latest models suggest interest rates will settle at a “neutral” level of about 7.25%, implying only one more 25bp rate cut in the current cycle.

“Consequently, the SARB’s latest decision appears to be a temporary pause in the current shallow cutting cycle rather than a definitive end,” Sprake says. “However, the scope for substantial further easing remains limited.”

Top image: Reserve Bank governor Lesetja Kganyago. Picture: Gallo Images/Misha Jordaan

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.